Above: Schwitters’ letter to his son explaining his plans for the Merzbarn, 20 September 1947. Courtesy of Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover.

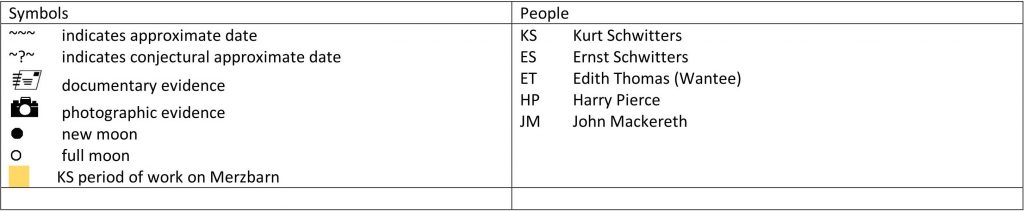

Timescale

Wantee told me in 1966 that Schwitters had been able to do about three months work on the Merzbarn. Allowing for some time when he was unable to work through injury or illness, this suggests he probably started at a date in mid-August 1947, possibly the 12th, when his doctor permitted him to work again after four weeks of rest after a bout of illness. We know that by 9th December his health had failed.

By report, he travelled out to Elterwater from Ambleside most days in that period except when confined to bed by illness, or was working on portraits and landscapes for sale. He had help from Mrs Thomas, Mr Pierce and Jack Cook who, according to Derek Carruthers, mixed the plaster for Schwitters.

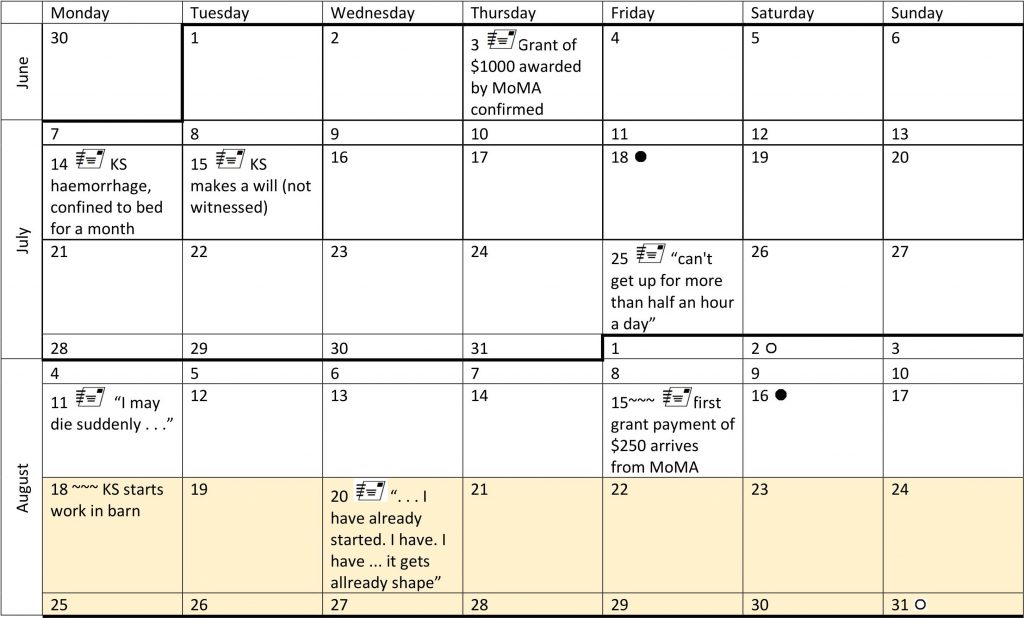

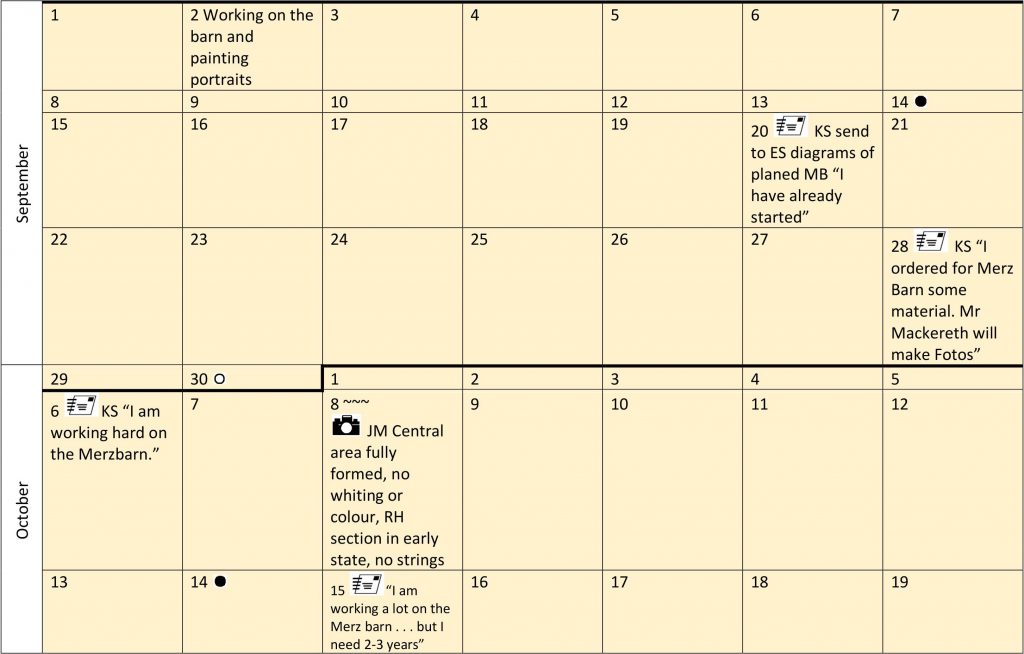

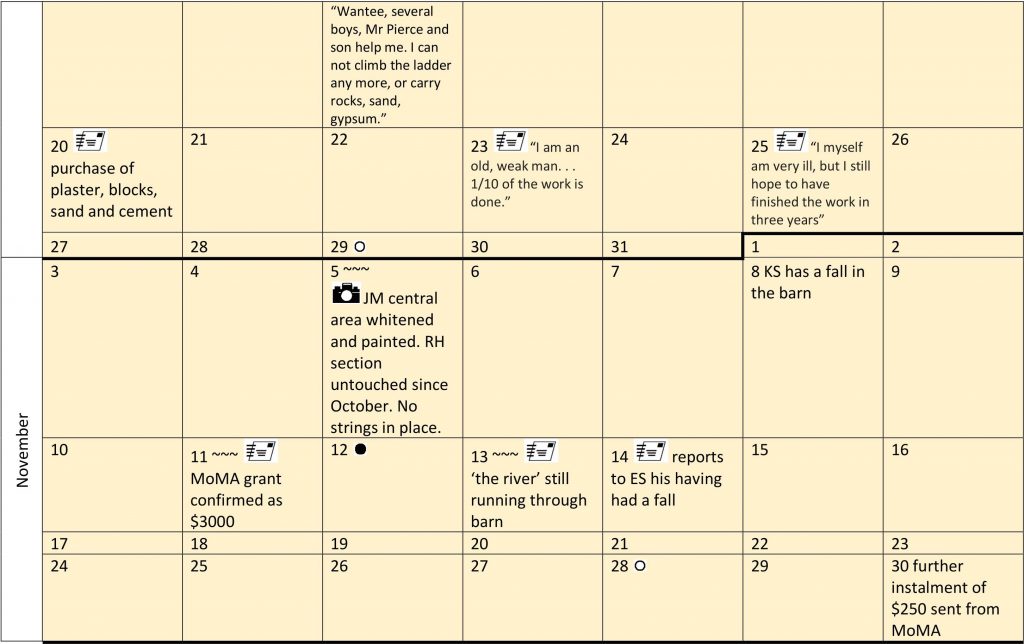

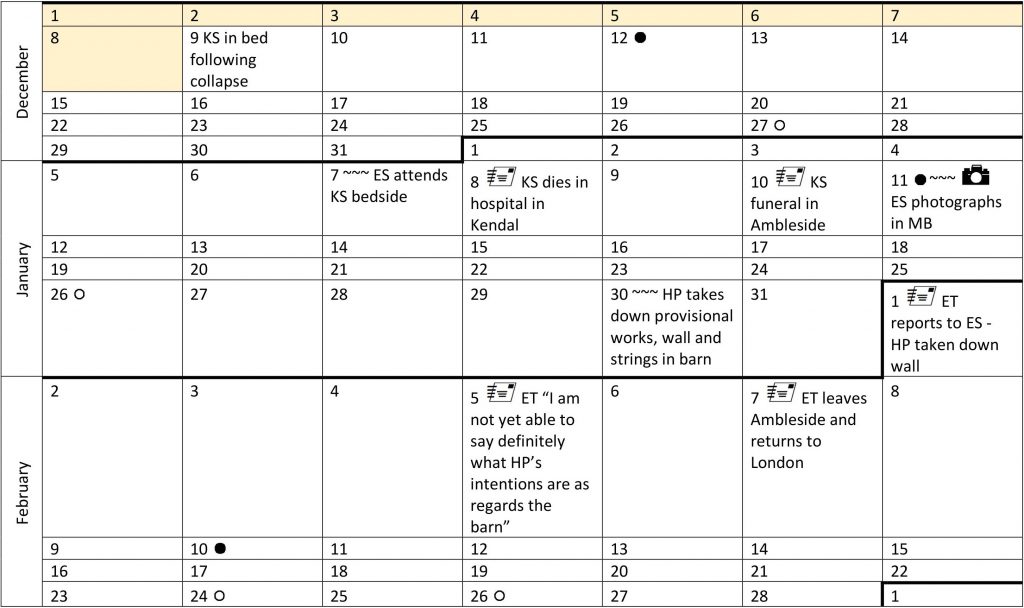

The calendar below sets out Schwitters’ short and intense period of work, ‘in feverish haste’, in what turned out to be the last few months of his life, though he did not realise this until close to the end.

Drawing on my own interviews with people who were there and other archive records, photographs and recollections, it is possible to assemble an approximate calendar of the creation of the Merzbarn.

Schwitters’ Merzbarn – calendar of construction 1947

“I myself am very ill, but I still hope to have finished the work in three years” KS 25 October 1947

Evidence

This section of the story reviews the available evidence, slight as it is, that throws at least some light on what happened. In the following chapter, on the basis of this evidence and from my own knowledge, what people involved told me, and the views of other commentators, I will attempt to put together an account of the making of the Merzbarn

Documentary Evidence

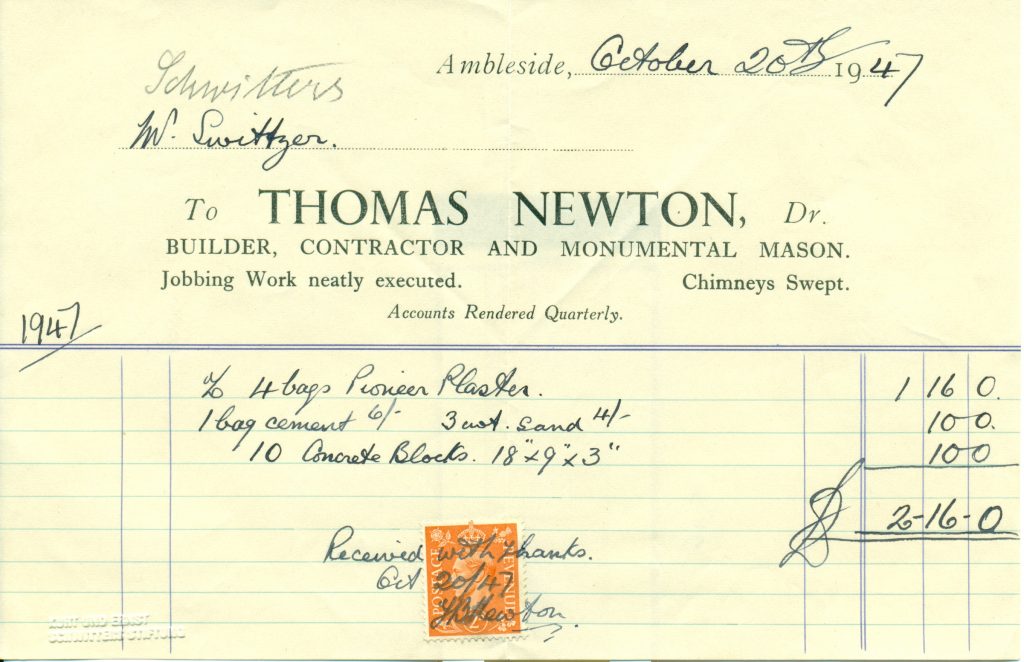

Materials purchased in October

In the Schwitters archive at the Sprengel there is a receipt for the purchase of plaster, sand, cement and concrete blocks from Thomas Newton, building contractor of Ambleside, made out to Mr Swittzer (corrected in pencil, in what looks like his own hand, to Schwitters). It is dated 20 October 1947, in the middle of his time working on the Merzbarn. This scrap of paper deserves some attention. It may not be the first purchase of materials, Schwitters says in a letter to Ernst on 28 September 1947 “Now I ordered for my Merz Barn some materials”, but it is as far as I know the only extant documentation of what Schwitters bought in, as distinct from found, at the time.

Courtesy of Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover

In detail, Schwitters bought:

- 4 bags of Pioneer plaster – £1-16s-0p

- 1 bag cement – 6s-0p

- 4 cwt sand – 4s-0p

- 10 concrete blocks, 18”x9”x3” – 10s-0p

- Total £2-16s-0p

A brief diversion into the Cumbrian gypsum industry

Plaster is the principal ingredient of the Merzbarn – it binds in the found objects, it is the material of all the relief sculpture across the wall, it bears most of the paintwork that was applied in the later stages. Like the stone of the barn, the plaster used by Schwitters might have been expected to have been a local mineral product.

Gypsum, calcium sulphate rock, (also known as alabaster too) was quarried, and later mined, in Cumbria over a long period, both as a material for carving and for whitening doorsteps. Though gypsum has been used since the ancient Egyptians, the plaster used in buildings was largely based on lime, until the early nineteenth century when the qypsum plaster industry developed rapidly on a large scale. The production of plaster involves crushing gypsum and heating it to drive off the water of crystallisation. The resulting powder will re-absorb water and set as a solid mass. This is the basis of plaster.

By the early 20th century several small local Cumbrian plaster manufacturers in Carlisle, Kirby Thore, Whitehaven and Long Meg had merged to become British Plaster Board. By the time of Schwitters’ work on the Merzbarn, BPB in turn merged with Gyproc in 1944 to become British Gypsum.

In 1966, working on the restoration, I sent a sample of the grey plaster that forms most of the substance of the artwork to the laboratory at British Gypsum in Kirby Thore, asking if they could analyse the material and identify it, which they kindly did. Their analysis identified the sample as Thistle backing plaster, one of their products, a brand still used by the company today. At that time, as I understand it, Thistle was produced from gypsum mined at Kirby Thore. I bought a bag, only to find it was not the grey I had been expecting, but pink in colour. I was foxed, and resorted to tinting the sculptor’s plaster we had in the Fine Art Department to match the colour as well as possible.

With the generous help of Ian Tyler, a distinguished industrial historian of Cumbria, I have now come to some understanding of what had happened. The raw material of Thistle plaster was mined from deposits which are stratified, and the colour of the eventual product after processing is dependent on the colour of the stratum from which it is taken. Over decades, as the mining worked its way down through the deposits of aeons, the colour changed. In Schwitters’ day, it was the neutral grey which he was evidently happy to use for much, almost all, of the relief work on the Wall. By 1965, the plaster was being produced from a pink stratum. One is bound to wonder what a different work the Merzbarn would be if he had happened to be working in a pink period.

Pioneer plaster

The purchase of Pioneer plaster, made in October, well in to the process of the Merzbarn, is however not the locally-made product. I am indebted to Nigel Bamping and Mike Jones of the Worshipful Company of Plaisterers for explaining its derivation. Pioneer plaster was made by ICI at its huge works at Billingham, as a by-product. From the early 1940s Pioneer was a low-grade plaster made from a synthetic calcium sulphate, itself a waste product of fertiliser production. Schwitters may have bought it because it was cheaper than the locally-produced gypsum plaster. The colour of Pioneer would be affected primarily by the impurities present in the calcium phosphate used as the prime raw material for fertiliser manufacture. It would probably have been an off-white colour.

It seems likely, then, that the Pioneer plaster was not used in the work on the Wall as we see it today, which is uniformly grey. The materials in this purchase, plaster, sand, cement and concrete blocks, were likely intended for the provisional work in the barn that was later removed. The purchase date, 20 October, may give a clue to the time when Schwitters began to realise his plans to develop the interior space.

Concrete blocks

The concrete blocks mentioned in the invoice would each have looked something like this  (a modern metric equivalent). The shape suggests that they would more likely be used in the wall structures that Mr Pierce mentioned, rather than in the column that stood towards the north-west corner. As a low wall, as Mr Pierce described it to me, and shown in Ernst’s photograph in January 1948, if laid five blocks high, about three foot nine say, even taking in to account the proposed niches, perhaps gaps between them, ten blocks do not amount to much in the scale of the layout in the barn.

(a modern metric equivalent). The shape suggests that they would more likely be used in the wall structures that Mr Pierce mentioned, rather than in the column that stood towards the north-west corner. As a low wall, as Mr Pierce described it to me, and shown in Ernst’s photograph in January 1948, if laid five blocks high, about three foot nine say, even taking in to account the proposed niches, perhaps gaps between them, ten blocks do not amount to much in the scale of the layout in the barn.

In the receipt alongside the blocks there is a quantity of sand and cement, which it might be assumed was destined to make the mortar to set the blocks. The order, however, suggests a very weak mortar of 8 parts sand to 1 cement (assuming a 56lb bag), and the quantity would lay many more than the 10 blocks purchased, in whatever formation they were used. Perhaps there were some blocks or similar materials already available at Cylinders, left over from another job on the estate maybe, and Schwitters was buying in a few more to make up what was needed. Perhaps this was a trial, and he anticipated buying more blocks if they worked out to suit his purposes, and got in enough sand and cement for the whole job rather than order very small quantities twice. We are, though, already nearing the end of October, with work well under way, so this may in any case be a supplementary order, topping-up the supply of material bought previously and already partly used up.

There is no evidence of the presence of sand and cement mortar in the Merzbarn itself, so one can assume that this purchase was related either to the parts of the planned interior construction of the artwork in the barn that no longer exists, the wall on the left or the column on the right, or to the work at the other end of the barn, related to the idea of a sales and storage room that Schwitters had outlined five weeks earlier in a letter to Ernst from his sickbed. Mr Pierce explained to me, in 1965, that the layout of the artwork’s walls within the barn was all quite provisional. I got the impression that blocks were stacked to form an indicative shape of the planned walls but that nothing was fixed, which if correct would suggest that the blocks were not set in mortar. Other commentators have referred to a full-height wall suggesting a more substantial structure. If that were the case, then at least we have some idea of what was used to build those parts. If one assumes that this receipt from Thomas Newton represents the materials ordered to be used in the construction of the diagonal wall, then it marks a point on the timeline of the development of the Merzbarn.

New evidence

For long the few photographs, recollected accounts and scraps of documents have been the only source of evidence for the making of the Merzbarn. Recently, in the conservation project that took place as part of the Hatton Gallery’s major capital work in 2016-17, a thorough and painstaking scientific examination and analysis has brought to light new evidence. I am grateful to Derek Pullen and Jackie Heuman of Sculpcons Ltd for the opportunity to include material from their extensive reports.

As part of the conservation work undertaken in 2016, a range of samples from the Merzbarn, including both those found on the site in 1965, and samples taken from the present installation, were analysed by conservation scientists Joyce Townsend and Tracey Chaplin. It becomes clear that the artist used a wide variety of materials, including artist’s oil paints, lower quality oil paint, perhaps student grade, industrial and commercial paints. He made extensive use of lead white and zinc white. The presence of alkyd resins suggests the use of household paints in some places. It is worth remembering that in 1947 England was still suffering post-wartime shortages. Food and fuel were still rationed, and among other privations, artists’ oil colours were hard to obtain. Schwitters’ correspondence with his son in Norway at this time shows him asking Ernst to send him paints and pigments in the post, which were apparently more readily available there.

The plaster underpinnings are mostly a commercial decorators’ plaster, but in areas worked to a smoother finish, plaster of Paris was used over the underlayers, sometimes over previous paintwork.

The examination by conservation scientists found that materials in the Merzbarn are consistent with those found in Tate’s late Schwitters sculptures of 1945-47, which included artists’ quality and industrial paints, oil and alkyd media, and plaster used to create forms. The range of colours in the Merzbarn is more restricted and the layering less complex, with fewer re-workings or changes of colour. The lowest layer in all sections tested in the central area of the Wall was found to be a rough whiting.

The chemical analysis conducted in 2016-17 revealed that in the central section of the work the substrate plaster had been covered with a layer of whiting (ground chalk) with an overlayer of zinc white paint. In my interview with Wantee in 1967 she explained to me that she had applied the white paint, which as I recall she said was white lead. Evidently one, or perhaps both, of us misremembered, as the recent analysis definitively identifies the material. This is also consistent with remarks in Schwitters’ correspondence with Ernst, in which he asks for zinc white to be sent him from Norway as it is hard to find in England, and Ernst posts a parcel of tubes.

The scientific analysis found that in some central areas where the surface is worked smooth and painted, plaster of Paris had been used for the upper layers, over the underlying grey. In the central area of the Wall all the grey plaster is covered with an undercoat of white or subsequent layers of paint. No raw grey plaster remains uncovered in this section.

All the evidence confirms that Schwitters was improvising, as he often did, using whatever materials he could get his hands on, doubtless aware that he had little time.

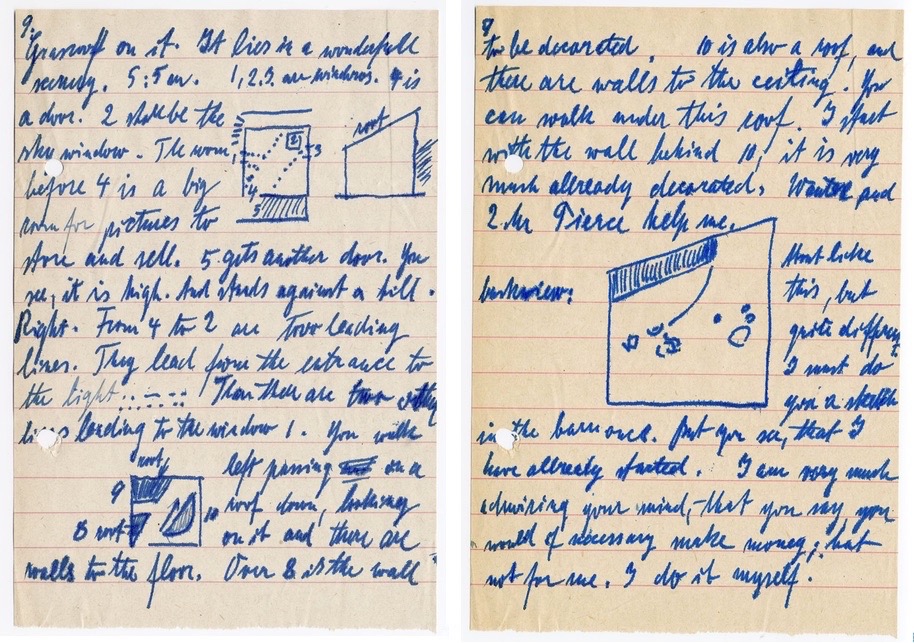

Diagrams

There is some additional visual evidence in the form of some tiny diagrams that Schwitters drew in a letter to Ernst on 20 September 1947. The extract below shows the relevant pages. A detailed analysis of these and a transcription of the text is given in the next chapter, dealing with what remained at the end of the artist’s life.

Courtesy of Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover

Photographic Evidence

There is very little extant visual record of the earlier stages of making the Merzbarn. What has surfaced so far are two photographs. Wantee mentioned to me in 1966 that Schwitters had arranged for photographs of the work-in-progress to be taken. She named John Mackereth as the photographer. This is confirmed by reference in a letter from Schwitters to Ernst dated 28 September 1947.

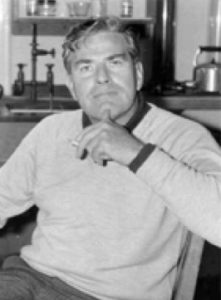

John Mackereth

John Mackereth at the Freshwater Biological Association laboratory at Windermere

I would like to make a brief diversion to consider someone who has had little attention from commentators, but who played a significant role in documenting the early work on the Merzbarn. Mackereth is a not uncommon name in England’s north-west, traceable back for centuries, and we know that Schwitters knew a Mackereth family, who had the outfitters and haberdashery shop in Central Buildings in Ambleside. He had painted a portrait of John, a son of the family, then about 25 years old. According to John Mackereth’s daughter in 2004, the family did not like the portrait, and Schwitters painted a landscape for them by way of compensation.

John, who had graduated in chemistry at Manchester, and then been a scientific officer on a Norwegian whaler, had lately been appointed as Principal Scientific Officer with the Freshwater Biological Association at Windermere, where he was to go on to have a very distinguished scientific career in the field of paleolimnology. Schwitters got to know him through the portrait and asked if he would take photographs of work-in-progress on the Merzbarn, to which John agreed. The portrait may have been a recompense for the photography project.

There are no photographs that can be definitively attributed to John Mackereth, as far I can discover. Taking in to account the content and the access to the work in progress that he evidently had, I conjecture that there are some images that can reasonably be considered to have been taken by Mackereth during the autumn of 1947.

Mackereth’s photographs

Some early-stage photographs of the Merzbarn-in-progress, probably taken by Mackereth, found their way to Stefan Themerson, emigré novelist, filmmaker, composer, publisher and philosopher. Schwitters had met Themerson in 1944 at the PEN club meeting to celebrate the three hundredth anniversary of John Milton’s Areopagitica, and became a close friend. Schwitters’ painted a portrait of Themerson in 1944, now in the Schwitters Foundation in Hanover. In 1948 Themerson and his wife Franciszka founded Gaberbocchus Press, which in January 1958 published Themerson’s book Kurt Schwitters in England 1940-1948, that contains two Merzbarn-in-progress images. My assumption is that before his death Schwitters gave the images to Themerson with the prospect of a publication, though this did not actually take place until ten years later. In 1966, when I was writing my degree dissertation about Schwitters, Themerson kindly gave me two prints of these early Merzbarn photographs. The Themerson archive now resides in Warsaw, in the National Library of Poland, the country to which his birthplace, formerly in Russia, now belongs.

The two images that appear in Themerson’s book seem to be the only extant evidence of the earliest stages of the Merzbarn, and they are not all that early. By my reckoning, from Schwitters’ correspondence, these were taken about a month or more in to the practical fabrication of the Wall, so perhaps late September or early October.

Photo: Themerson Archive, National Library of Poland, Warsaw

The illumination is low sunlight that comes from the south window, consistent with the time of year. The sweeping curved ridge running towards the top right, the emerging forms of the top ridge and the long wedge shape suggest that the decision to lead the composition towards the upper right corner of the room was already determined. The skylight may have been in place by this time but there is no sign of light from that source or the north window.

Already the main features of the central area are in place, but at this point no whiting or colour has been applied. Much of the right-hand section is still bare stone wall. A small iron ring hangs from the projection at upper right that does not appear in later images. The top ridge is at an early state. A horseshoe-shape element located at this time at the space in the middle of the top ridge does not appear in later images. There is no stringing from top ridge to door present at this point. The small items that were placed inside the rectangular metal frame are not yet in place. The u-shaped tile below the wheel arc is not yet there.

Photo: Themerson Archive, National Library of Poland, Warsaw

Ernst Schwitters’ photographs

In December Schwitters’ time ran out. On 9th December he was confined to bed, breathless. Shortly afterwards he was admitted to hospital and did not return to the barn again. The nearest we have to evidence of the state of things when Schwitters left off the work is a few photographs taken by Ernst Schwitters.

The photos are not precisely dated but it is understood that Ernst visited the Merzbarn at some point after the funeral of his father that was held on 10 January 1948, and made these images. He also took some exterior photographs at that visit, but it appears that only these four of the inside survive. These images tell tantalisingly little.

Photo Ernst Schwitters, January 1948: Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover, courtesy Kurt and Ernst Schwhitters Stiftung, Hannover.

Perhaps the light was poor (there was no power available for lighting), perhaps he was so upset by the death and the funeral that all he wanted to do was take a picture of his late father’s hat in situ. Perhaps this is Ernst’s own hat, a kind of ‘Kilroy was here’ moment before he left, or is it Mr Pierce’s or Jack Cook’s hat, taken off and hung up while setting about clearing the barn, or even had Schwitters an intention to include the hat in the artwork, in one of the ‘grotto’ parts? One cannot say, but this is all we have.

Photo: Sprengel Archive, Hanover

There is nothing here to illuminate what had been going on at the north side of the barn to the right of these images, where Harry Pierce described to me in 1965 there had been a ‘column’. Further uncertainty is cast on these images in that they may not in any case represent ‘how Schwitters left it’. By this time he had not been there for a month, and the process of clearing and removing the unfinished parts may well have been already under way. Elements that appear in these images are not necessarily in the place they were the last time the artist touched them, or where he intended them eventually to be. We will never know.

What can be seen

The photographs are taken inside the barn from a more or less central position looking towards the left centre area of the mural on the far wall (the west wall, now in the Hatton). The Wall appears much as we see it today. The scene is generally dark, with a low, strong light from the south window illuminating in sharp relief some structures that no longer exist, having been removed by Harry Pierce not long after these pictures were taken.

Some of the strings that ran from the top ridge of the mural leftwards to the entrance doorway, that are known from contemporary reports and visible evidence today, can be seen in these photos. It looks as if long strips, some plasterboard (used elsewhere in the mural) and some wood, are lying across the web of strings. The farthest strip lies with one end on the top ridge and the other resting on the strings. Going to the left, several more strips are laid across the strings aligned more or less from the south window towards the middle of the room, their edges strongly illuminated by the light from the window. These are not obviously ordered or fixed. On top of them lies a paper bundle and a Spry Shortening tin. One of the strips shows a lump of plaster that suggests it was previously attached to something or to the floor. At the inner end of this group of strips there is a roughly plastered object, something like the size and shape of a Coke bottle, that appears to be set on the end of one of the strips of plasterboard.

Below and behind the strips is something catching a strong light from the window. This appears to be a tall board of some kind set more or less vertically, and to have some plasterwork on its surface at least in the lower part. Something not visible casts two bars of shadow across the upper part.

Coming closer to the camera there is a tall standing V-shaped form. The felt hat hangs on the right-hand leg of the V. This form is made from two long, slender square-section sticks of wood, joined by some plasterwork at the point where they cross. The plasterwork is more solid below the crossing point in the form of a tall pyramid shape out of the top of which grows the V. The two lengths of wood that cross at the point of the V continue down making the shape of the pyramid. The floor level at this point is not shown in these photographs, but it might be inferred that these two sticks stand on the floor. They create a long narrow pointed and twisted shape similar to some of the forms in the Hannover Merzbau.

Closer still to the camera, the landscape format shot shows a complex group of forms. There is clearly, if a little out of focus, a wall about four foot six high. It appears lumpy and irregular, so may not be built of the concrete blocks Schwitters had bought in October, though what is visible may be plaster overworking. Its irregularity and its uneven top make it difficult to be sure in what direction it lies, but it evidently comes across from the left, where the doorway is, and stops short somewhere in the vicinity of the window. This is broadly consistent with Schwitters’ sketch in his letter to Ernst of 20 September 1947. Continuing east from the end of this wall there is an extension which shows a horizontal element, a shelf, above what looks like a void lying between the end of the wall and the upright plank shape. There is some material on the shelf, including a stick protruding out from it horizontally. On top of the wall lies a three-pronged construction, a recumbent pyramid in shape, that appears to be made, in a similar way to the V, from three sticks bonded together with plaster, leaving much open space between them. The apex encloses the left-hand upright of the V, and the tip of this construction aligns with the innermost string, which may be attached to it.

A Conundrum

The photograph below was taken by Ernst Schwitters during his visit in January 1948, alongside the ‘hat’ photos shown above. The image is poorly framed, and there is flare from the central painted areas, uncharacteristic of a professional photographer like Ernst. Nonetheless, as Isabel Schulz at the Sprengel has helpfully pointed out, this image must be contemporary with the ‘hat’ images, since it exists on the same strip of negatives.

Photo Ernst Schwitters, January 1948: Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover, courtesy Kurt and Ernst Schwhitters Stiftung, Hannover.

This image shows the central part of the Merzbarn. It has its coat of whitening, and the paintwork is in place. The right hand section, shown in part, is clearly in an earlier state than we see it now. The lower ridge curving up to the right is not present. Parts of the bare wall that are now covered with plaster are visible and the uppermost of the three iron rings can be seen, hung in place before it was plastered over. The uppermost part of the top ridge leading towards the skylight is different from the state we see now, showing one of the sticks that form its armature, and other parts of the top ridge are narrower, showing more of the stonework behind. In the lower left corner is what appears to be two bags or sacks each tied at the neck, one on top of the other, possibly bags of plaster or sand.

There are some apparent contradictions between this and the ‘hat’ images. It is helpful to have Isabel Schulz’s account of the strip of film which bears these images.

“It is a 35 mm Kodak Safety Plus film. The sequence of the 6 pictures with the numbers 23-28 of the strip is as follows: 2x indoor shot with hat (landscape format), 1x indoor shot with hat (upright format), 1 outdoor shot Merz Barn in the terrain, 1 outdoor shot of the Barn from a distance (with tree in front left), and as the last picture of this strip the questionable shot of the relief wall. The previously taken pictures 19-22 of the same film are 2 pictures of Schwitters‘ fresh grave as well as 2 outdoor pictures of the church in Ambleside, so that the dating to January 1948 is secured.”

That the arrangement of sticks and the low wall visible to the left in the ‘hat’ images are not seen in the final image can be explained by the photograph being taken from closer to the wall. However, the web of strings which were attached to the top ridge of the artwork at one end and to the wall near the door at the other (the extant remains of which I have seen for myself) are present in the ‘hat’ images, but not in this final image. The chair, which is visible in the ‘hat’ images, is not present. Furthermore the light falls rather differently in this compared to the ‘hat’ images, which do not show the flare, and in which the shadows are not cast in the same way.

The absence of the strings, not to mention the chair, is distinctly puzzling. How could this be? Because the negatives are on the same strip does not necessarily mean that they were taken on the same occasion. Ernst did not leave the area immediately after the funeral. He could have visited the barn more than once, and we might be looking at a later image in the last frame. This could explain the difference in the light. It is not inconceivable that for the last shot he passed the camera to someone else, a less able photographer.

Alternatively, and seemingly more likely, if these images were all shot on the same visit, the sequence of the negative strip tells that he went in to the barn, took some pictures, went out and photographed from outside, at some distance, and then went back in to the barn. Perhaps at this time Mr Pierce was in the process of taking down the ‘provisional’ parts of the work, better to reveal the Wall, and he took down the strings while Ernst was outside (perhaps moving the chair to stand on it so as to reach the top ridge and snip off the strings). Ernst came back in and photographed the wall again, without the strings. We know from correspondence that Ernst agreed with Mr Pierce over the removal of the incomplete parts, to the later disappointment of Wantee, and agreement must have been reached in a conversation at some point during Ernst’s time in the locality. This group of photographs may show the moment when that happened.

I know from my calculations of the position of the sun that by the time Ernst returned to the barn, the light was failing, it would have been getting dark inside. It is feasible that Ernst used a torch or lamp of some kind, possibly held by Mr Pierce or Mr Cook, to take a hurried last shot before photography became impossible, which might account for the poor composition, the flare and the different fall of light.

The evidence is slim and uncertain, and these are hypotheses. What is certain is that Ernst saw the barn after his father’s death, not necessarily in the same state as Schwitters left it, and took a few photographs which show that change was under way. This is indicated both by the sequence of images inside the barn, and by the pile of aggregate outside, confirming that Mr Pierce’s plan to prepare the Merzbarn for exhibition was already under way.

Ernst was not to return to the barn for several years, date unknown, probably in the 1950s. By then the Merzbarn was into a cycle of events, public exhibition alternating with storage, which is reviewed in detail in Chapter 5.