Above: Receipt for purchase of materials, ‘Mr Swittzer’. Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover

On the basis of the limited evidence that is available, some tentative conclusions can be drawn about the making of the Merzbarn. One day then, probably in mid-August 1947, Schwitters begins work in the barn.

There is no record of this, one must use some imagination. Picture Schwitters, a big man, six foot two, coming in to the empty barn to make a start. To me it looks like he begins by addressing the west wall, opposite the door, where the best light is. There is the wall, about fifteen feet wide and ten high, stones roughly laid with gaps and crevices. Schwitters we know was a hoarder, an artistic hunter-gatherer, and so has about him from early on a collection of stuff he has picked up from the garden and the yard, on his journeys out from Ambleside and his walks in Langdale. He has some basic tools, and some bags of plaster, bought in locally. How to begin to tackle this new canvas? Since the new roof did not get put on for a while, with the skylight, his light would have been mostly from the south window on the left, so the concept of the work building towards and articulating the light from the top right-hand skylight will have come a little later.

Picture Schwitters, a big man, coming in to the empty barn to make a start.

He had in mind the earlier Merzbauten, fully spatial environments, and so to get off the more-or-less two-dimensional wall into the third-dimension space would, it seems to me, have been an early priority. Technically, given the circumstances, there were few ways to do this. What he seems to do from the start is to take the opportunity of the unevenness and irregularity in the wall’s structure to wedge things in to gaps so that they break the plane, sticking out into space. Signs are that early elements put in place in this way included some metal rod, that may be a section of a grid, wedged in and bent into shape to form the armature of two elements (the yellow blob on three rods and the brown wing-shaped form adjacent); a coiled strip of metal (painted red) of which one end is embedded in the wall and the other supported on a block fixed to a plate wedged in to the stones, and another piece of wood (perhaps it is a stone.) There are several more pieces of wood in this central area including one on which sits the small metal frame that isolates a crevice where other items would later be placed. Further to the right is a group of iron rings that initially hung on nails knocked in to wooden pieces wedged in the wall, later to be plastered over.

Methods

Having little or no construction equipment and limited time and means, the method that lent itself to Schwitters’ creative process owed a lot to the nature and form of the building itself.

I think he began by wedging objects into crevices in the wall, leaning things up against it, trying to secure things with nails, string and wire before plastering them into place. Gradually layers were built up across the face of the wall, leaving some areas rough from the tool, bringing some parts to a smooth finish as forms and relief areas developed. Almost all of the found objects were eventually covered with plaster and or paint. Most were used as armatures for the creation of forms and shapes and are buried in the plaster, while a few retain a visible identity. It appears from the few photographs of work in progress that much of what we see today was built up to its current shape in plaster, before colour was applied at a fairly late stage in the process.

It is perhaps worth looking in some detail at elements of the artwork to examine how Schwitters’ working methods and the raw materials interact. In several places, there is a resonance with those parts of the Hanover Merzbau where over the long period of work, early collage and assemblage became embedded and framed by later overlay. The Merzbarn of course did not have the span of time for that process of accretion, but there are some hints. In the left centre of the Merzbarn, a small rectangular steel frame is plastered on to the stones of the wall. This was originally plastered over and painted, but had rusted and shed its covering by the time of removal in 1965. While the surrounding area is plastered and painted, within the frame the stones of the wall, with a large crevice between them, are revealed, painted and populated with some small found objects, the spout of a little watering can, a white stone, a couple of small pieces of wood. To the right, part of an oval wooden gilt picture or mirror frame is similarly plastered to the wall, the stones within its curve and the gap between them revealed and populated with found things, a bunch of string, a conical seashell.

In some instances elements are fabricated from pieces of wood and then wedged between the stones of the wall to fix features of the composition. In several places a strip of plasterboard is leant against the wall and then plastered in to place. At the foot of the wall at the right-hand margin of the whitened area, where a plasterboard strip leant against the wall, there is an infill of small stones, bits and pieces, with some plaster bonding, possibly drawn together from the original earth floor.

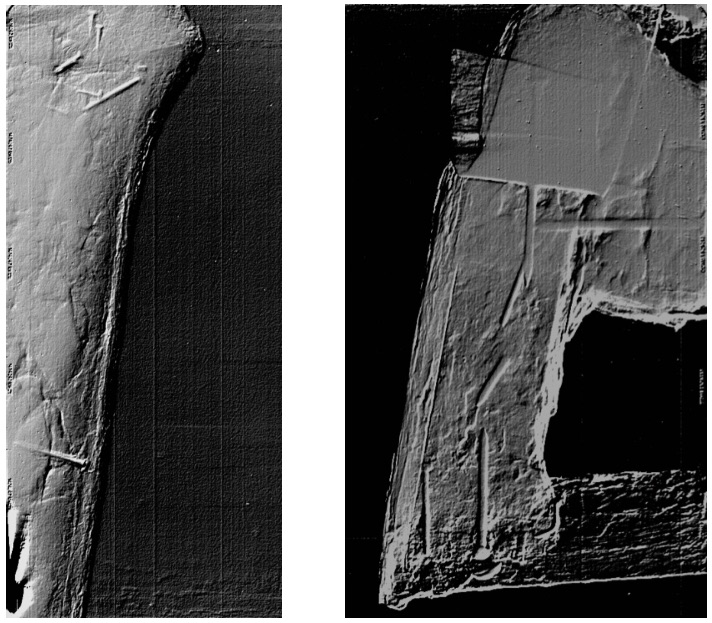

When one of Mackereth’s photographs taken at a relatively early stage is overlaid on to an image of the Wall as it is now, one can appreciate something of the process and sequence of the work. To do so involved some juggling with the perspective to get the images to align. The result is below.

Nails

Famously, the artist declared “My name is Kurt Schwitters…I am an artist and I nail my pictures together…” The x-ray photographs made for conservation work in 2016 clearly show that several elements of the relief are indeed nailed together.

Photos: ©Colin Davison 2016

Right: Yellow bracket with red painted metal spiral. The bracket appears to be made from wood with clear evidence of nails. Left: Red painted wedge shape made from wood. The x-ray shows it has at least 7 nails and tacks embedded. Photos: Sculpcons Ltd

Right: Yellow bracket with red painted metal spiral. The bracket appears to be made from wood with clear evidence of nails. Left: Red painted wedge shape made from wood. The x-ray shows it has at least 7 nails and tacks embedded. Photos: Sculpcons Ltd

Small sculptures

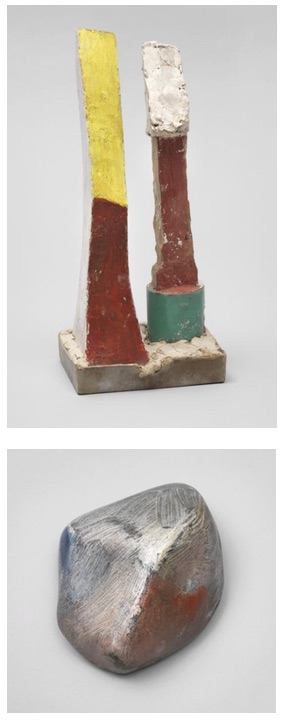

At the same time as working on the Wall, Schwitters was working on a series of small sculptures, some of which were intended to take a place in the Merzbarn. Several of these are in the Tate collection and have had the close attention of conservators there.

Their construction casts some light on the Merzbarn itself. In these the artist uses found objects as the starting point, sticks, stones and other bits and pieces. The sculptures are worked over repeatedly, both modelling up the forms, applying and sanding off the plaster, painting and repainting. The Merzbarn follows a similar trajectory. Found objects (including the wall itself) form the underpinning of the development of form and rhythm using plaster and paint. Schwitters mentions in a late letter that he is no longer able to do the work of sanding down plaster, this then being done by his assistants, confirming that this is part of his process on the Wall as well as on the small sculptures. The Merzbarn can be seen, in one sense, as the biggest of these small sculptures, whose scale means that the degree of re-working and overpainting is less than in the small hand-sized works, but whose process and formal development is closely connected.

Above left: Untitled (Togetherness) c. 1945-7 Below left: Untitled (Stone) c. 1945-7. Photos: Tate Gallery. Images released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

One day, perhaps, the Tate’s collection of small Schwitters sculptures will be brought to the Hatton and exhibited alongside the Merzbarn. That would make it possible to see how these connections are manifested.

What was there at the end

At the time of his death, the Merzbarn was a work-in-progress. The west wall had had most attention and was in a more complete state than the later parts to north and south that were still provisional and in transition. The evidence is slim, but it is worth some speculation, as far as the evidence will carry it.

The composite image below combines Ernst’s image with the Merzbarn as we see it now, and gives an indication of the way the last elements that Schwitters made, now missing, related to the earlier parts of the work.

Photos: ©Colin Davison; Sprengel Archive

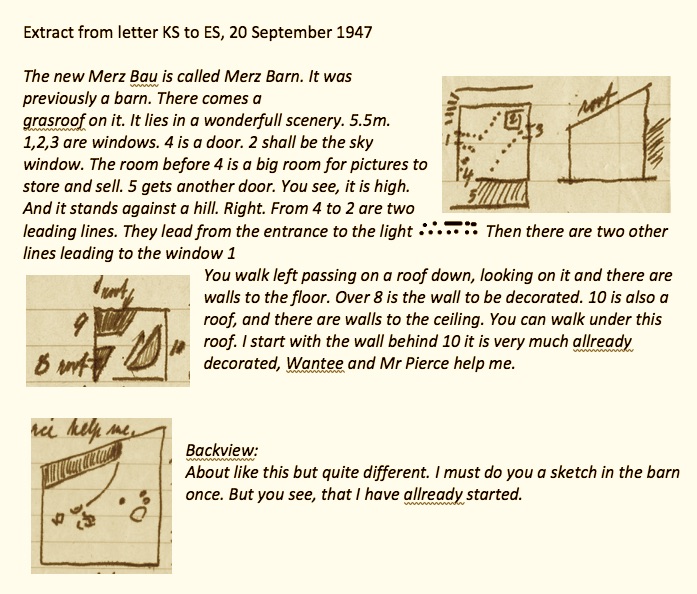

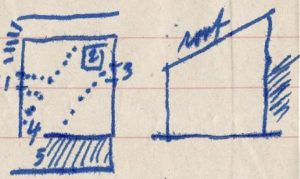

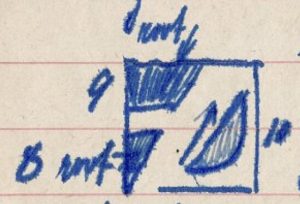

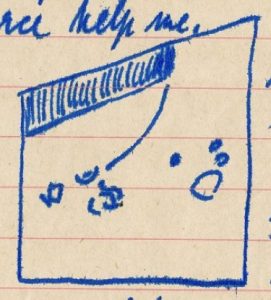

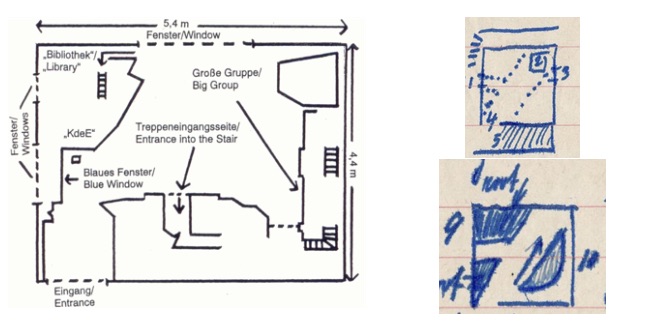

It is enlightening to refer from this image to the diagrams in KS’s letter to Ernst of 20 September (courtesy of Sprengel Archive, Hanover.) Transcribed, it looks like this:

In the first plan, the ‘leading lines’ to the left of the room are broadly consistent with what the photographs show.

The low wall that appears to lead from the doorway to the vicinity of the window aligns pretty well with the first part of the left line, the tall V-shape could mark the beginning of the second half of this line, as the space between it and the end of the low wall is in the right place to admit light from the window.

The low wall that appears to lead from the doorway to the vicinity of the window aligns pretty well with the first part of the left line, the tall V-shape could mark the beginning of the second half of this line, as the space between it and the end of the low wall is in the right place to admit light from the window.

The third diagram plan shows ‘roofs’. One has to be careful in interpreting exactly what the artist means by a ‘roof’. Schwitters says in relation to roof 8 that ‘you walk left passing a on a roof down, looking on it, and there are walls to the floor’. This suggests that the roof shown at 8 is at a low level, and that would be consistent with the run of the strings, and with what Schwitters says later in the letter, referring to roof 10 (which is at the high side of the room), ‘you can walk under this roof’, suggesting that one could not walk under all of them.

The third diagram plan shows ‘roofs’. One has to be careful in interpreting exactly what the artist means by a ‘roof’. Schwitters says in relation to roof 8 that ‘you walk left passing a on a roof down, looking on it, and there are walls to the floor’. This suggests that the roof shown at 8 is at a low level, and that would be consistent with the run of the strings, and with what Schwitters says later in the letter, referring to roof 10 (which is at the high side of the room), ‘you can walk under this roof’, suggesting that one could not walk under all of them.

Entrance to the barn showing plasterwork to the right of the doorway, which bears the ends of strings that once stretched across the room. Photo: FB

He also says that ‘over 8 is the wall to be decorated’, suggesting that the new wall, and the space behind it is roofed over at a low level. There remains in the barn a patch of plaster dabs adjacent to the door jamb (right). Within this are the remaining traces of the strings. There are no signs remaining of a diagonal wall having been built out from this part of the barn.

Roof 9 does not get a mention in the text of the letter. From the composite image above it looks fair to assume that the area where the strips and planks rest on the web of strings would correspond to No 9. One can see in the composite the place in the leftmost corner where the top ridge meets the return wall, that a shelf-like form, made of sticks and plaster, is built across the corner. This can be seen as the beginnings of the fabrication of roof 9, which would be a development of the existing top ridge which would have extended much more deeply across the space of the interior.  At its right-hand end it would be high enough to walk under but not at the left. This is consistent with the elevation diagram in the same letter that shows a shaded-in area above the top ridge.

At its right-hand end it would be high enough to walk under but not at the left. This is consistent with the elevation diagram in the same letter that shows a shaded-in area above the top ridge.

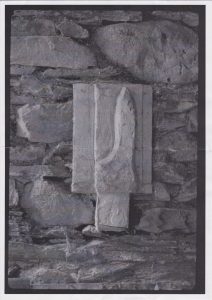

Small wood and plaster relief, as seen on the North wall of the barn in 1965. Photo: Mark Lancaster

Roof 10 has ‘walls to the ceiling’ and, he suggests, ‘the wall behind 10 it is very much already decorated’. This is a puzzle. We have no documentary evidence of that side of the room, and there was no visible artwork on it in 1965, other than the small plaster relief mounted on a wooden block wedged in to a crevice, now missing (left).

Schwitters was writing from his sickbed at this point, and the letter itself has a confusion in his page numbering. I think he makes a mistake. He means to refer to the wall below 9, rather than behind 10. In other words what we now know as the Merz Barn Wall. That would not explain the ‘behind’ which suggests that 10 is a freestanding element, as the diagram in his letter shows. Is what is indicated at 10 what became ‘the column’? Looking back from the mid-1960s, Harry Pierce described separately both to John Elderfield and to me that a substantial element of the interior of the Merzbarn was a ‘column’, situated somewhere towards the north-west corner, leaning towards the skylight. Elderfield and I each drew similar conclusions about the location from what Pierce told us.

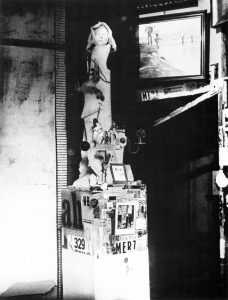

Hanover Merzbau, Merz-column, 1923(?) photo: Wilhelm Hoepfner

Both he and I took ‘column’ to mean something more or less cylindrical, but in the light of other work that Schwitters called a säule (column or pillar), as in the Merzbau (left) and Hjertoya (right), it may have been nothing of the kind.

Die Grosse Merzsäule. Photo Schwitters

There is no extant evidence of the column in the Merzbarn, no photograph exists as far as I know, and it does not appear explicitly in Schwitters’ diagrams of September. There was little to be learned from Mr Pierce about the construction or nature of the column. It is conceivable that the column would have formed part of the support to roof 10 at its north-west end. No specific mention was made to me by Mr Pierce of any such roof structure being present when Schwitters left off work in the barn. It seems possible that the column was an idea that developed later in the process, extending beyond the proposals set out the 20 September letter.

It is worth noting that the letter of 20 September makes no reference to the web of strings that was set up spanning the interior of the barn from the west wall to the doorway in the east wall. The strings were certainly there by the end, Mr Pierce specifically referred to them in his description to me of what he took down, and the evidence of their presence is still there both in the Wall and the barn. I take it to be that Schwitters set up the strings later, in October probably, as a way to implement some of the outline plans set out in the letter. His improvisatory way of working would suggest that the plans in the letter were subsequently varied and extrapolated in the practical process, and that the process itself sparked further invention. There is more examination of this question in the appendix.

Echoes of the Merzbau

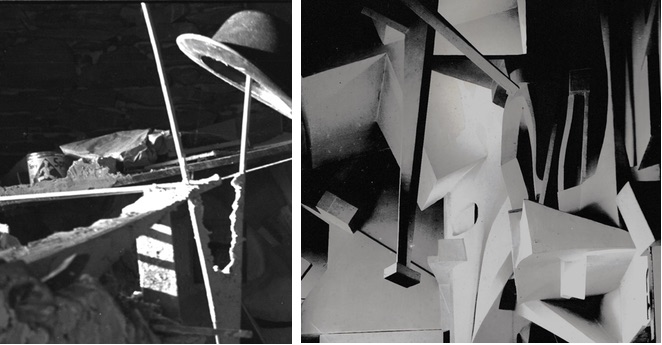

Ernst’s images of January 1948 give some clues to Schwitters’ methods of fabricating elements of his three-dimensional artworks. The upright V and the recumbent pyramid shape in the Merzbarn (left) both show the form being built from slender lengths of wood that are plastered together where they cross. It looks as if these might have been put together initially on the flat, before being set up or joined to other elements, as the plaster at the joint of the V that has an irregular inside profile, is sharply cut off and aligned with the edges of the wooden strips. There is a hint here of the way some of the characteristic forms in the Hannover Merzbau may also have been fabricated.

It is interesting to compare the layout of the Hannover Merzbau with Schwitters’ little diagrams of his conception for the Merzbarn. The plan on the left is from the Sprengel’s Catalogue Raisonné, those on the right from Schwitters’ letter to Ernst of 20 September 1947. The resemblance is intriguing. I understand that some parts of the Merzbau were freestanding, with an access between the sculpture and the wall behind it. This has a parallel with roof 10 in the Merzbarn. There is no extant documentation or recollection that confirms it was ever realised as such, but it was clearly in the artist’s mind that even in such a confined space there could be hidden places not at once revealed to the spectator.

Light

Light, as other commentators have pointed out, was an important element in the Hanover Merzbau and in the barn, and it is worth giving the topic some attention. The barn had four windows, none of them large, one in the middle of the south wall, a smaller window high up against the roof in the north wall, the skylight over the northwest corner and the tiny glazed panel in the door jamb. When we arrived to make the survey, light was very restricted. The south aspect was heavily shaded by trees, though these did not exist, and so would not have been such a barrier, at the time Schwitters was working. The north window gave on to the slope behind the barn which was quite overgrown when we arrived. That prospect may have been more open at the time of Schwitters’ work, but would in any case have been a north light and the pane is quite small. The skylight is evidently of significance since Schwitters asked for it to be installed when the roof was renewed. From what can be seen in the shape of what survives, and from reports of the provisional layout and Schwitters’ intentions expressed in letters at the time, the light coming in from this source was to be a strong element of the composition of the work as a whole. When Schwitters was working, it is probable that the south window was the principal source of daylight, particularly as the seasons advanced.

As Mr Pierce and I stood in the barn, he described to me the outline of a sloping diagonal wall aligned south-east to north-west, which was provisionally laid out with some stacked concrete blocks. This was cut back to the left to allow in light from the south window. Similarly the curved ceiling set out provisionally with strings was to have an opening in some form to bring the light in from the south. Mr Pierce recalled to me that Schwitters spoke about including electric lighting in the Merzbarn, as he had done in Hanover. The idea Mr Pierce described was to include lamps behind the upper ridge of the work on the west wall, not directly visible, casting a downward light over the relief. Schwitters would likely have had ideas too about illuminating some of the planned niches. There was, however, no power supply, and the team worked by candlelight as the days darkened.

It was pretty gloomy in the barn when the survey team visited it in May 1965. My abiding memory of it is seeing the central section, that had been treated with a white pigment, glowing, appearing to float in the gloom, against the darker-toned areas to either side. In that context, when I later learned more of Schwitters’ intentions, it was stimulating to think of what he might have done had a power socket been available.

Rectifying a misapprehension

A minor point. In one or two sources I am reported as having said that the interior walls of the Merzbarn were whitewashed or plastered during Schwitters’ time there. Either that is a misinterpretation of something I once said or I was talking nonsense, and I would like to take this opportunity to set the record straight. At the time of my work there, beyond the actual artwork itself, the stonework was bare, there was no general plastering or whitewashing of the stone walls in the interior of the barn where the Wall is located.