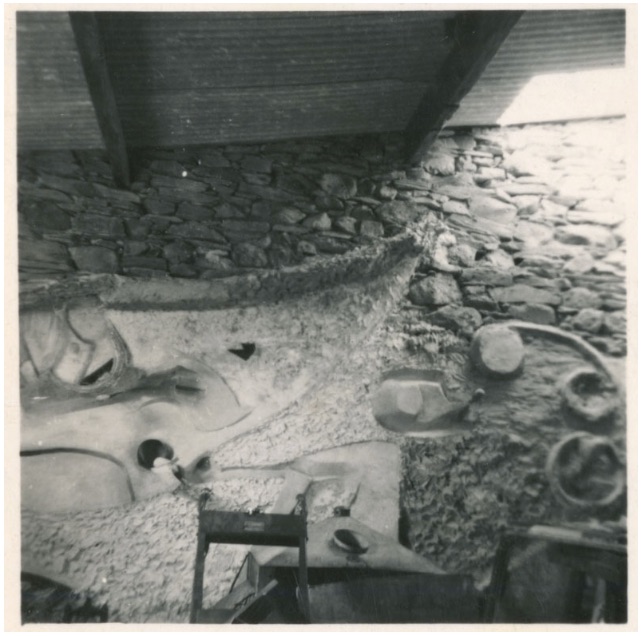

Above: Merzbarn in situ, 1950s, photo Ernst Schwitters. Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover, courtesy Kurt and Ernst Schwitters Stiftung, Hannover

By April 1948, Mr Pierce had the barn in shape, and opened it to the public with an exhibition of smaller Schwitters works displayed alongside the Wall. In May Pierce wrote, and Gwyneth Alban Davis typeset, a small brochure for visitors which was published as The Abstract Art of Kurt Schwitters, The Story of the Merzbarn. I am grateful to Bill Davis for permission to include it here.

Reproduced by courtesy of Bill Davis

In the ensuing seventeen years the Merzbarn would be at different times open to the public, sometimes visited by appointment, sometimes, being used as a storeroom, effectively closed. From what can be seen in the extant photographs, and taking in to account testimonies and recollections, it is possible to draw at least an outline of the further adventures of the Merzbarn between 1948 and 1963. It is worth bearing in mind that during much of that period Schwitters was virtually unknown in the UK, not so much forgotten, as hardly having been visible in the first place. In the locality no connection had been made with the RCA when that opportunity might have been taken. He had made something of an impact with local residents, principally though his personal charm and his naturalistic painting, and he and Wantee had made some friends. After his death, and Wantee’s departure, he was remembered locally as that rather eccentric German artist. In the closer circle of artists and people with a particular interest in modern art his work was recognised, he had exhibited his abstract work in London and was hailed by Herbert Read among others as a significant pioneer. The Merzbarn, though, far away and little documented, scarcely figured in the art world’s appreciation of his innovation. It was not until more than a decade later, in the late 1950s and early ‘60s that artists and the art establishment began to discover it.

In the barn, efforts to promote and preserve the Merzbarn ebbed and flowed.

In the barn, efforts to promote, and indeed to preserve, the Merzbarn ebbed and flowed. Harry Pierce’s aim to realise the visitor potential of the Merzbarn evidently had limited success. It is an irony that the barn has seen far more visitors since the Merzbarn was removed from it than was ever the case while it was there. In the 1940s and ‘50s even in the art world his work and association with Dada were seen as old-fashioned and of little interest. So it is not surprising that opening the barn to visitors was not an immediate success, though nonetheless there were visits.

Waxing and waning

It becomes clear that the effort to create an exhibition lapsed over time. It seems that after Ernst Schwitters later returned to the barn and took away many of the smaller works, it began to return to its original purpose as a store for the estate. Barbara Crossley recounts that a further attempt was made by Mr Pierce to make the Merzbarn accessible in 1955 when he opened his garden to the public.

The state of the floor, as well as of the artwork, throws some light on events. The photographic evidence shows that there were times when the floor was swept and the space around the Wall kept clear. This was evidently the case when Ernst Schwitters visited the barn, which he did on more than one occasion after 1948. It was also kept clean and tidy in the period when the Merzbarn was open to visits by the public. It is clear from some accounts that there were times when the barn was ‘dressed’ to appear that the artist’s studio had been preserved untouched. This is factually not the case, since the work-in-progress at the time of Schwitters death had all been removed early in 1948, but points to the effectiveness of Mr Pierce’s efforts to make the barn as interesting as possible to visitors. No less a visitor than Mary Burkett was impressed, recollecting her visit with some of her students in Autumn 1958;

Over the doorway of the shed we approached was a piece of carved wood in the form of a snake, and we knew at once it must be the right place. We cautiously pushed open the door. I can remember well how we all stood still with a mixture of shock, awe and delight. In front of us was a bench on which there were a few paint brushes, a palette, a paint rag and other objects. Beyond was the Merz Wall glowing in the faint sunlight that filtered through the cobweb-covered windows. It was such a strong atmosphere that we whispered. It was as if the artist had slipped out and would come back at any moment, yet he had died ten years previously. Mr Pierce had kept the barn carefully and not moved anything.

At other times the state of the floor as it appears in photographs shows that the barn was not expecting visitors, that it was primarily a garden store.

Mary Burkett OBE 1924 – 2014

I would like to take a moment to acknowledge the debt of gratitude owed by me, and everyone with an interest in Schwitters’ time in England, to Mary Burkett. Mary came to the locality in 1954 as an art lecturer at Charlotte Mason College in Ambleside having no idea that Schwitters had lived there, indeed in the same flat she was living in herself. Having discovered locally something of his time and work there, she and several students visited the Merzbarn in 1958. Mary moved to a position at Abbot Hall Art Gallery and Museum in Kendal, under Helen Kapp, herself succeeding as director in 1966. Mary tirelessly researched and promoted Schwitters’ period in Cumbria and mounted pioneering exhibitions of his work. I recall that she followed the Merzbarn in her car as it left Cylinders and took a photograph of the groove that the low-loader left in the crest of Clappersgate bridge.

Mary Burkett's vigour and dedication laid the ground for Schwitters' recognition in Cumbria

Mary traced many of Schwitters’ works that had come into the possession of people in the area during his time there, wrote articles and exhibition catalogues, and built the Abbot Hall collection. Her vigour and dedication laid the ground for the way that Schwitters’ work in Cumbria is recognized and valued today. This portrait by Carel Weight features a poster for one of her Schwitters exhibitions.

© the artist’s estate/Bridgeman Images. Photo: Lakeland Arts Trust

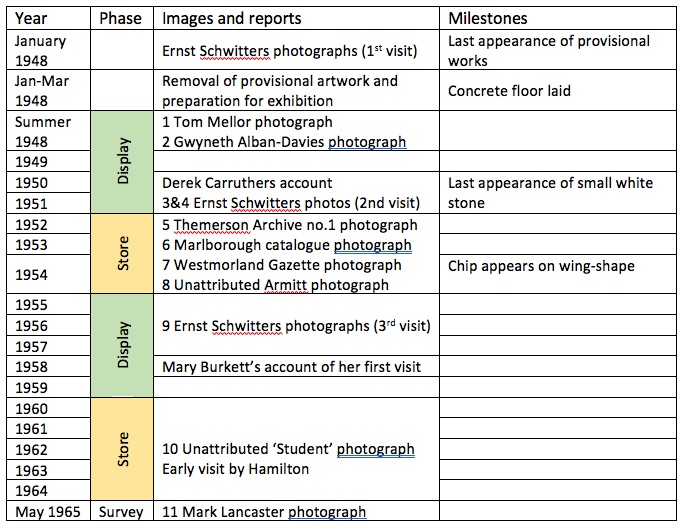

Sequencing images 1948 to 1965

Reliable attribution and dating is very scarce among the scant photographic evidence for what happened to the Merzbarn over the period from the first opening to the public up to the survey to prepare for the removal. After much struggling with some twenty-four factors that vary between the extant images of the Merzbarn, I think I have come to a more or less robust account of the sequence of events. Dating is necessarily uncertain, and I will be grateful for any additional light that can be cast on this period.

Evidently there were periods of time when Harry Pierce sought to exhibit the Merzbarn and other Schwitters works, and other times when the barn lapsed back into being a storage shed for Cylinders. From my analysis of the extant evidence, it looks to me as if there were two periods when Pierce was promoting the exhibition idea, in the late 40s-early 50s and again in the mid-to-late 50s. By the end of that decade, institutional interest in saving the Merzbarn was rising, leading eventually to its removal. In the early 50s and again from the late 50s to the early 60s, while it still had some visitors, the barn was primarily a store. The calendar looks something like the following.

Merzbarn calendar 1948 to 1965

This tentative dating is based on detailed examination of extant photographic evidence together with the few contemporary accounts and recollections that are available. It is far from definitive. Comment and challenge are welcome. I hope that by publishing this provisional calendar, further knowledge and analysis may be stimulated.

Selected images in sequence

Photo: Tom Mellor 1948, courtesy of Gwendolyn Webster

Image 1 In summer 1948, a matter of weeks after the Merzbarn was first opened to the public, on a visit the architect Tom Mellor took this image of a group of Schwitters works brought out of the barn by Harry Pierce to be photographed. The group includes the sculpture Chicken and Egg 1942 (on the table) and the right-hand of the two works on the wall, Untitled (White Construction) 1942, both now in the Tate. Leaning against the flowerpot is Ohne Titel (Glas auf Stein) 1947. The crescent-shaped beck stone appears in other photographs and was still in the barn in the 1980s. To the right of the stone is the painted assemblage Black Powder (1945-7) also now in the Tate. The square format and limited resolution suggest use of 120 film in a box camera.

Image 2

Photo: Gwyneth Alban Davis

Gwyneth Alban Davis took this photograph, showing the barn set out with a display of artworks. Schwitters’ Chicken and Egg stands on a pedestal. A framed artwork (not recognised as by KS) is on the wall, and what might be two small sculptures on the table. The floor is swept. An armchair, a wooden trestle (which appears repeatedly in images through to 1965) in the left foreground and some other unidentifiable objects are present. Possibly this is in the period when used as a studio by another artist, around 1950, as reported to me by Derek Carruthers in 2019.

The artist Derek Carruthers was born and raised in Cumbria. He was later a fine art student at Newcastle (then University of Durham) under Victor Pasmore. As a 14- or 15-year-old he visited the Merzbarn. Carruthers’ father had mentioned his son’s interest in modern art to Mr Pierce, who invited Derek to see the Merzbarn. Derek explained to me that at that time, in 1950 or ‘51, two or three years after Schwitters’ death, another artist was using the barn as a studio. Derek was impressed by the Merzbarn Wall and aware that it was part of a larger work that would have occupied the space more as an environment. He also noticed several Schwitters art works including relief sculptures, in his words, ‘lying about’ looking somewhat neglected. On a later visit, Derek met Jack Cook and discussed the artworks with him. Cook mentioned having taken some of the reliefs from the barn for safe-keeping from the damp, and stored them under his bed. These were taken away by Ernst Schwitters on a subsequent visit.

Image 3

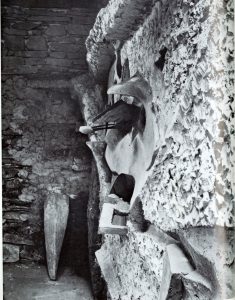

The Merzbarn, undated photo: Ernst Schwitters, Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover, courtesy Kurt and Ernst Schwhitters Stiftung, Hannover.

One of a suite of five colour images attributed by Sprengel to Ernst Schwitters, located in the Ernst Schwitters Archive. Taken by natural light apparently, from all three windows. The high resolution and square format suggest a medium format camera was used for all of this set, which also helps confirm the attribution. This suite is the best photography of the Merzbarn in this pre-removal period that has at present surfaced.

Some flaking of paint and plaster on decaying plasterboard at lower right might suggest a later date, but there is no evident decay of the central painted area, and the green paint on the wheel arc appears intact. The small white stone is present in the small metal frame. The brown wing-shape does not show the chip that appears later. The floor is clear of ancillary articles and plant pots, and appears as if recently swept. This too would confirm the attribution to Ernst, as Mr Pierce would likely have cleared up the barn in preparation for his visit.

Image 4

Photographer unknown, Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover

This is a good-quality photograph that has both detailed definition and a long depth of field, which tends to confirm Gwendolen Webster’s attribution to Ernst Schwitters (though the Sprengel tentatively attributes it to Noel Forster). It is not one of the images taken in January 1948, since the strings and upper works then still in place are not present. It appears to be taken in daylight, with shadows cast from the skylight and the north window, suggesting summertime. There is what appears to be a chalk mark on the floor adjacent to the foot of the club-shape sculpture, which is the other way up from the image above.

I think that this and the image above were both taken by Ernst on a visit to the barn some years after the death of his father, probably about 1951. It appears in different sources differently cropped. It is quite possible that Ernst was using more than one camera and film, and that this image was not taken in the same square format as the colour images, but without access to the negative it is impossible to be definitive.

Image 5

Photo: Photographer unknown, Themerson Archive, National Library of Poland, Warsaw

This image from the Themerson archive in Warsaw is a poor-quality, badly-composed, square-format image. It shows some articles in the barn in front of the Wall, including a lawn mower and a large object having a pyramid-shaped top, with a hole, possibly a flue. It is evidently from a ‘storage’ rather than ‘display’ period. There is little visible decay. Possible dating from shortly after the first ‘display’ period ended, perhaps about 1952.

Image 6

Photographer unknown, Themerson Archive, National Library of Poland

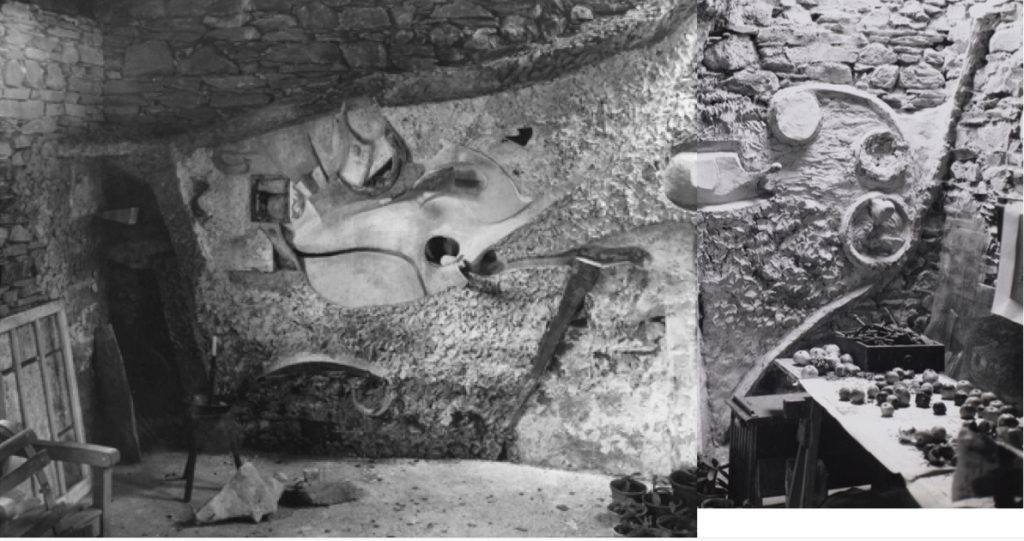

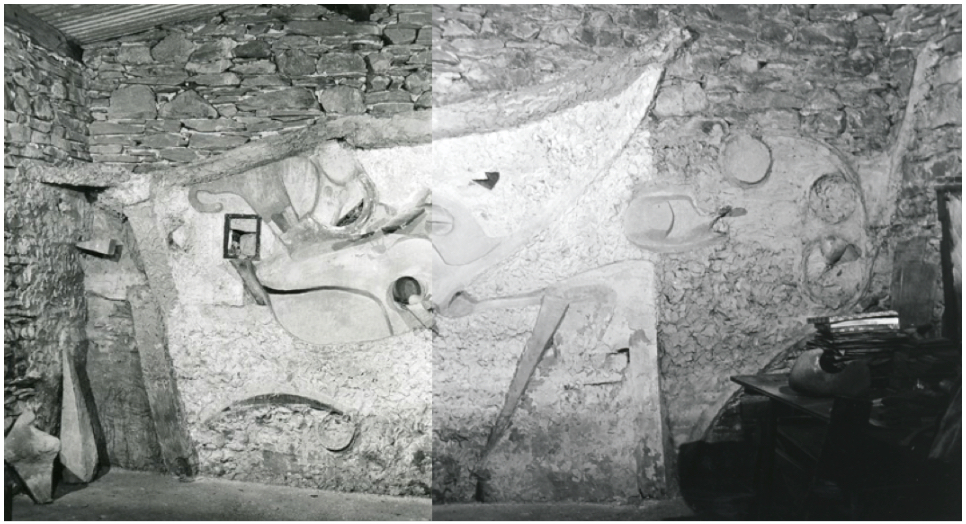

Photographer unknown. This is a combination of two images from the Themerson archive in the National Library of Poland. The Marlborough Gallery catalogue of 1981 attributes the left-hand image to Ernst Schwitters with no date. It is combined here with an image from the Themerson archive also uncredited and undated, but evidently from the same set.

Shadows indicate that the scene is lit from all three windows, implying daylight rather than artificial. Standing in front of the wall is Schwitters’ candlestick, according to the Marlborough. At the left-hand wall an object is leaning, that looks like the club-shape sculpture seen in this position in other images. A large sculpted object and a stone lie on the floor in front of the Wall. The sculpted object is also present in 9. Extraneous objects in view are a glazed window pane, two wooden benches (one also present in 8 below and the other in 11 and outside the barn in 1965), and some flower pots with plants growing in them. The trestle with table-top is visible as in 7 and 8, here bearing apples for storage, suggesting autumn or winter. A drawer full of metal articles is visible on the tabletop, that also appears in 7. Something that might be an artwork hangs against the wall at far right. The floor is not swept. The little white stone in the small metal frame at left of centre is not present, but the tip of the brown wing-shape to the right does not have the chip that is present in later images. Possible dating around 1953-54 during the ‘store’ period before the second ‘display’ began about 1955.

Image 7

Photo: Westmorland Gazette, courtesy of Derek Carruthers

This image, kindly made available to me by Derek Carruthers, is credited to the Westmorland Gazette, and was probably taken about 1953-54. It is a good quality image taken by natural light from all three windows. The white stone is not present, decay is evident in the plasterboard and around the gilt frame. The small metal frame is quite extensively rusted. The chip on the tip of the brown wing-shape can be seen.

In this ‘storage’ period it is clear that the Merzbarn is cohabiting with other aspects of work on the Cylinders estate, but evidently visitors might still be expected. The small painting that sits on a bench at the left is by Schwitters, View of Buildings at Cylinders, dated 1947. His candlestick is also on the bench. There are numerous pots of plants, presumably sheltering here for the winter, and the tabletop on a trestle, on which is a fuel can that also appears behind the trestle in 6. At the lower left is the edge of the galvanised bin that also appears in 11 and outside the barn in 1965.

Image 8

Photographer unknown

The same painting appears in this image which was found on the website of the Armitt Library by Gwendolen Webster, but is as yet unattributed and undated. A tabletop resting on the same trestle again supports various objects including another painting, unidentified.

Image 9

Photographer unknown , Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum Hannover.

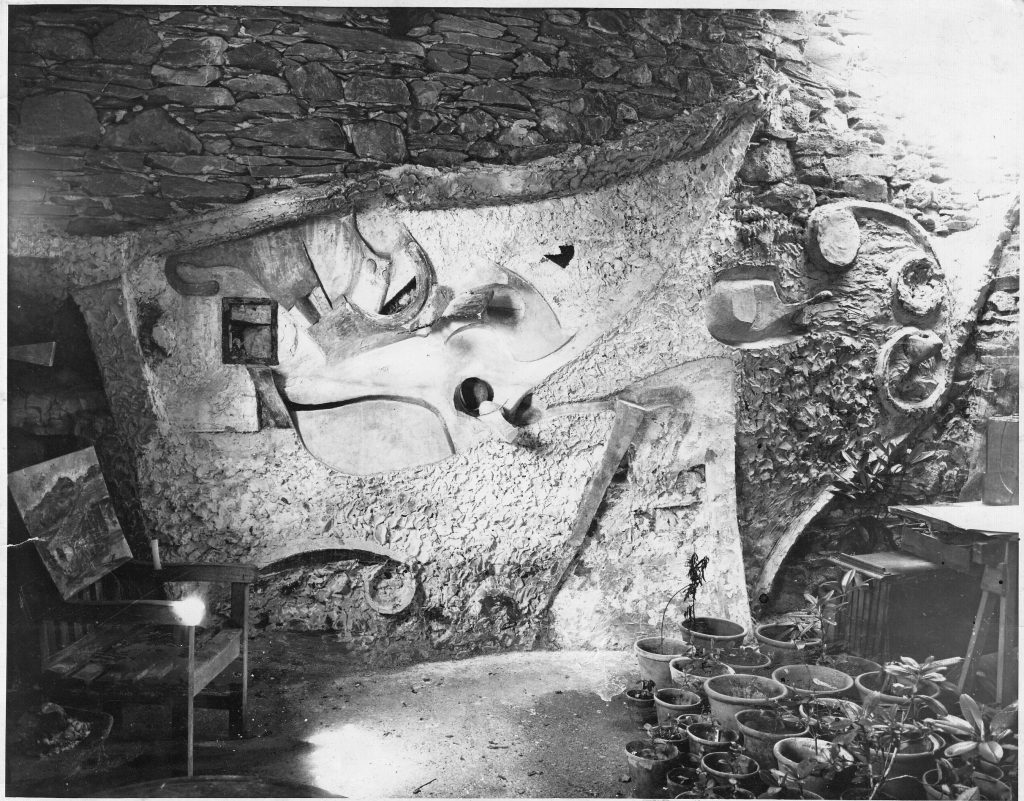

This is a pair of unattributed and undated images from the Ernst Schwitters archive at the Sprengel, which show a panorama of the Merzbarn at this point. The illumination suggests that artificial lighting was used. Good quality and square format suggest a skilled photographer, so these were probably taken by Ernst on one of his visits after 1948. The presence of the concreted floor and plaster spur on the right-hand wall means this was taken after Schwitters’ death. Decay evident in the plasterboard elements and in the gilt frame area, suggests a later rather than earlier date. Lying on a trestle, the tabletop with books might indicate that this was taken during period of ‘set-dressing’ after Schwitters’ death, possibly about the time of Mary Burkett’s visit in 1958. The crescent-shape beck stone also appears in other images and was present in 1948 and 1965.

The pair image is clearly taken at the same time and by the same photographer. This image shows two sculpture pieces leaning against the left wall, both of which are present in 6 above. The small metal frame shows extensive rusting and loss of paintwork. The small white stone is not in place, but something that might be it sits on the top of the red wedge-shape below the frame. The chip on the corner of the brown wing-shape shows clearly. The floor is clear of stored articles though not quite swept clean.

Image 10

Photographer unknown, Tate Archive © The estate of Edith ‘Wantee’ Thomas

Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

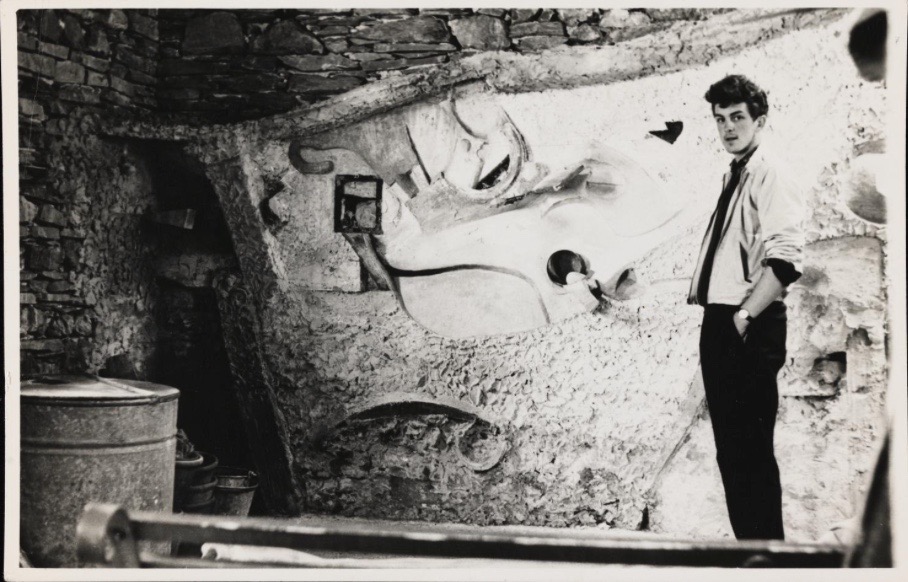

Tate gives the date 1963 for this photograph, donated by Wantee’s son Geoff Thomas, with a title referring to a ‘student’. If the date is right, this may be an image from one of Richard Hamilton’s early visits prior to the Merzbarn being gifted to the University. However, no-one of that generation of students at the Fine Art Department in Newcastle that I have been able to contact recognises the man in the photograph, so it may be from another source altogether. It is possible that this is one of the suite taken by Noel Forster for the Arts Council in 1960, who may have taken a fellow student with him on the commission.

The small white stone in the metal frame is not present, the chip on the brown wing is visible, there is extensive decay. This image shows a bench (also present in 6) facing the Wall as if for viewing, a bucket, flower pots and a large galvanised tub, apparently stored here. The tub and bench appear outside the Merzbarn in a photograph taken in early 1965 which helps confirm the date.

Image 11

Photo: Mark Lancaster 1965, Hatton Archive

A general view of the Merzbarn taken by Mark Lancaster in May 1965 as part of the survey for Newcastle University. A foot-scale for the survey photography is marked out in chalk on the floor, and our calibrated measuring stick is visible at far left. The trestle is still present. The barn was at this point cleared out inside. Another image from the same series (below) shows the position of the south window.

Photo: Mark Lancaster 1965, Hatton Archive