Above: Merz Barn Wall being lowered into the Hatton Gallery, 20 June 1966, photo Fred Brookes

Negotiations were concluded, the deed of gift was signed, the money was raised and the project to save the Merzbarn was ready to move from a plan to a reality. This section deals with how that was achieved and how the Merz Barn Wall was moved.

Once the gift had been agreed, Border Television produced a report on the plans. A brief excerpt of this interview survives as an archive insert in the Arts Council documentary film I Build My Time, made by Tristram Powell and narrated by William Feaver in 1975. It features a clip from the interview with Mr Pierce in the barn, and also Wantee, Edith Thomas, returning to Cylinders. A brief extract from the film can be seen here.

There is a link to the complete documentary in the links section.

Preparation

Condition and the plans to preserve the Merz Barn Wall

By the time the deal to relocate the Wall was done a further opportunity was taken to examine its condition and survey it. In May 1965 under the direction of Richard Hamilton, three students of the Department (Mark Lancaster, Stuart Wise and me) undertook an extensive survey of the Merzbarn, making countless photographs, drawings, measurements and colour matchings, collecting up fallen fragments of the surface and amassing as much data as possible. This was to ensure that, should the Merzbarn be damaged on its journey, it would be possible to restore it, or even reconstruct it completely.

We found that the fabric of the work had deteriorated badly. There were several reasons why this had happened, despite Mr Pierce’s efforts to preserve it. The wall on which the greater part of the plaster relief was laid was a Lake District-style drystone wall. This is typically a double wall, two leaves of stones leaning slightly inwards, with intermittent long stones, ‘throughs’, laid to tie the two leaves laterally. Each stone is sloped slightly downwards from the middle to allow rain to run out. There is an infilling of rubble and small stones filling up the space between the inner and outer leaves. There is no bonding mortar or any other adhesive material, the wall is held together only by gravity. In this instance the stone used is irregular, much of it fieldstone, with little or no dressed stone, so the wall is uneven and has gaps and crevices. These were a boon to Schwitters, providing the means to fix found objects and materials that provide much of the work’s structure. In the longer run, the potential for ingress of damp and the possibly of movement in frosty conditions was exacerbated by the fact that on the outside the lower several feet of both the west and north walls were covered by an earthen bank, which kept the building more or less damp most of the time, and particularly in rainy weather. This, combined with freezing in winter, meant that much of the plasterwork was in poor condition by the 1960s. In the central area of the wall, which received the most extensive treatment, Schwitters and his assistants laid on plaster, progressing from rough application with a knife or trowel to successive layers increasingly compacted and sanded smooth. Eventually these areas were painted, again in layers, using oil paints. Over time, with the repeated cycles of wet, dry and frost, some of these areas delaminated. The upper layers of thin plaster and paint spalled away from the substrate, forming a fragile shell with a shallow void behind it. This shell had in many places broken away, and our survey found much of the painted areas of the work in fragments on the barn floor.

Another complication was that a layer of white pigment had been applied to most of the central area of the wall. Later, Mrs Thomas explained to me how she had done this part of the work applying the pigment with a brush in what seems to have been a more or less raw form. Recent scientific analysis suggests that the material was not white lead, as Mrs Thomas recalled, but zinc white and whiting (ground chalk). We know from Schwitters’ correspondence that his son sent him a consignment of colours including zinc white around this time. When we saw the wall in the 1960s, while the heightened tone of the area treated in this way was clearly discernible, it was equally evident that, over time, much of the part treated in this way, that had not been overpainted, had fallen off. What had once been white was now a slightly lighter tint of the grey plaster from which the work was built.

Survey images

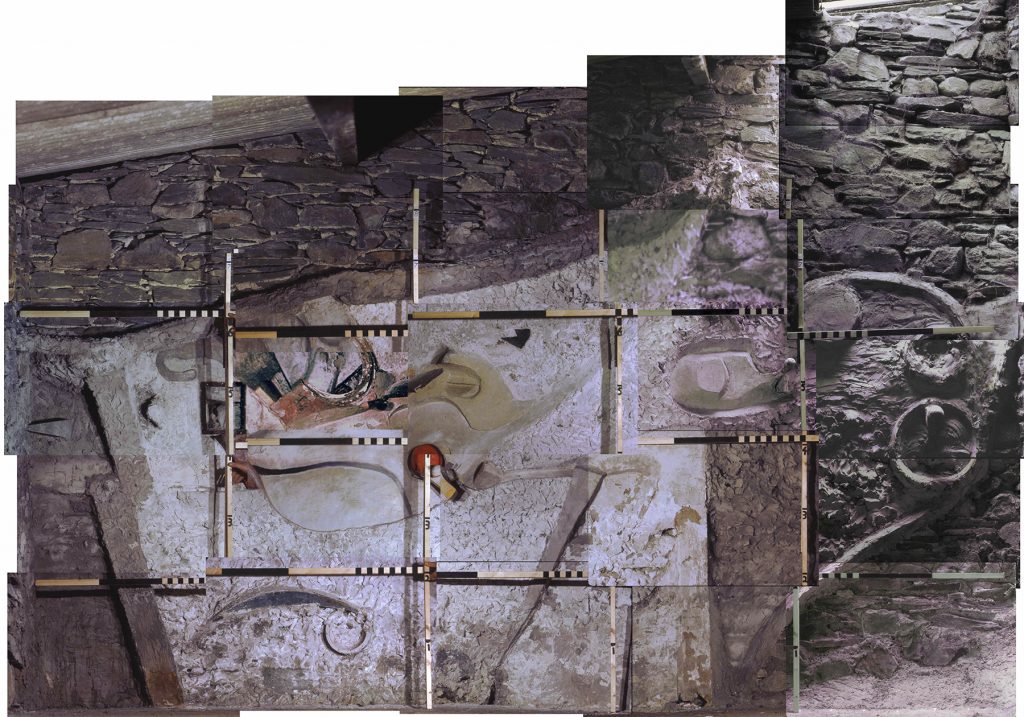

Mark Lancaster led on photographing the Merzbarn as it then stood in the barn, making a portfolio of shots of the artwork and its surroundings. The wide shot below shows the chalk marks on the floor we used to make a systematic coverage of the whole surface of the wall, using a pair of measuring sticks and photographing in three- by two-foot segments, in colour transparency. The barn had at this time been cleared out inside. Fortunately for us in the survey team, the floor had not been swept, and we were able to retrieve and identify many colour samples from the fallen fragments.

Photo: Mark Lancaster 1965, Hatton Archive

The slides, now in the Hatton archive, have begun to degrade over time, and the colour balance is now out of kilter. I have assembled a mosaic using the best available slides of each segment. It gives a previously unseen account of how the Merzbarn was in May 1965.

Compiled mosaic of survey photographs. Photos: Mark Lancaster 1965, compiled FB 2019. Hatton Archive

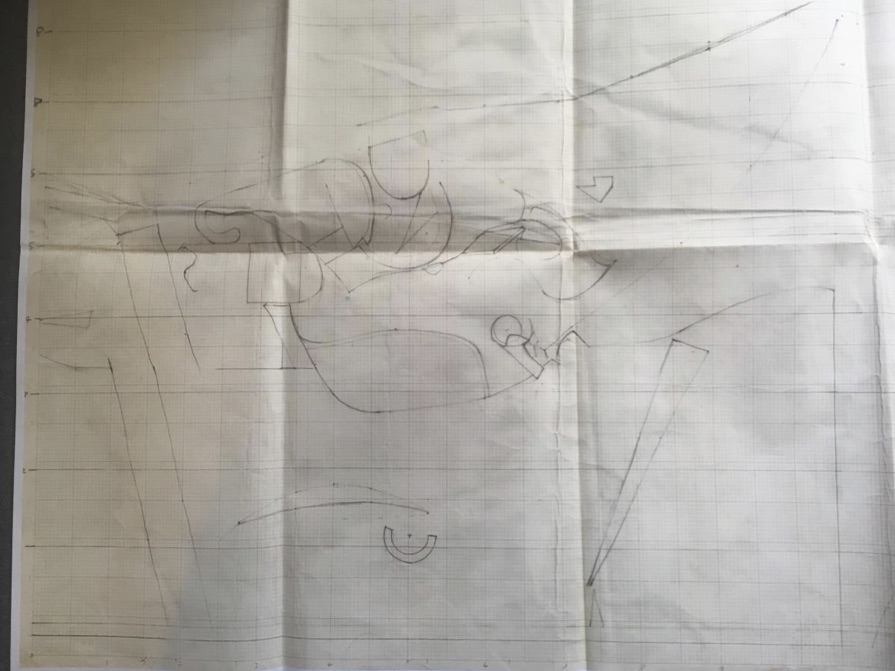

The scale drawing that I made, gridded so that each sample could be located, looked something like this.

Drawing: Fred Brookes, Hatton Archive

Preparation for removal, and the new building at Newcastle University

Long before the agreement to move the Merz Barn Wall was reached, the architects Sheppard Robson had been commissioned by Newcastle University in 1959 to build a range of new buildings in the area between the former Armstrong College and Claremont Road. Alas not by what would have been astonishing foreknowledge of the Schwitters connection yet to come, the first building, the Applied Science and Mathematics department, was named Merz Court. Not for Schwitters, but after one Dr Theodore Merz, author of A History of European Thought in the Nineteenth Century.

- The Hatton Gallery’s new entrance and the Fine Art Department building, in 2018. Photo: Colin Davison

- The Merz Court building. Photo: University of Newcastle upon Tyne

Later the Sheppard’s contract was extended to include a large new extension to the Fine Art Department that would include new spaces for the Hatton Gallery. The whole extension was built on stilts to enable passage at ground level through to the interior areas of the development and the passageway known as Eldon Place. The Hatton, that has since been remodelled twice, most recently in the capital development programme of 2016-17, was originally formed of two wide corridors linking the old and new parts of the building, with a suspended platform between them intended as an outdoor sculpture display area, with large plate-glass windows looking on to it. The outdoor platform has since been roofed over and incorporated into the Hatton’s gallery spaces. With the Merzbarn’s removal in view, a place needed to be found for it to be permanently installed. I have not been able to trace any of the architects involved in planning for the Merz Barn Wall. What I think happened was that the design work for the new building was already well advanced and construction more or less under way when the opportunity of the Merzbarn came about, and the architects were asked to work in to the existing plans a place to accommodate a new, large, heavy and as yet unknown artwork. The site was chosen in the north corridor of the Hatton extension, and an additional alcove was designed, cantilevered out from the wall at second-floor level, constructed in the same cast concrete as the rest of that section. Dimensions must have been provided in the specification, though no record of what was specified has so far turned up. The upshot was that a wide, shallow box-shaped space was built out from the north side wall, a shuttered concrete construction with supporting stub beams, floor, back and side walls, open to the air at the top. The intention was to drop the artwork in from above and then roof it over. In the end the space created was generously tall and wide, but the front-to-back depth would cause some problems, as we shall see.

Moving the Merz Barn Wall

This account of the removal and restoration of Kurt Schwitters’ Merz Barn Wall from my point of view, here extended and re-edited, was originally written in 1966 for Quarto, the magazine of Abbot Hall Art Gallery, when Mary Burkett was its Director. Mary, alas now no longer with us, was early to recognise Schwitters’ significance and his place in the art history of Cumbria, and was a great encouragement to me in the work I did there.

Except where otherwise credited, the photographs in this chapter were taken by Fred Brookes in 1965 and ’66. Copyright in these images, and the associated diagrams, also by FB, resides with the Hatton Gallery, Newcastle University.

Harry Pierce, the Merzbarn’s owner, signed a formal Deed of Gift to the University on 26 March 1965. The gift was made on the understanding that it would be removed to a new location, restored and preserved. A scheme of operations for the removal was devised, funds were raised and contracts agreed. On 12 July 1965, the contractors John Laing of Carlisle, moved in to begin operations. I, having been involved in the survey, was sent by the University to look after its interests in the artwork.

Securing the Wall

The problems of the removal were manifold. The primary problem was the fact that the work was a plaster construction applied directly to a dry-stone wall that stood against an earthen bank.

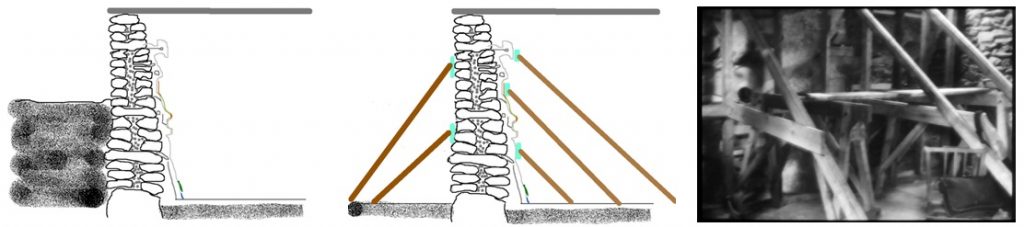

The nature of its construction meant that the wall could not be taken apart and reassembled at its new site, it could only be moved in one piece. It was decided that the best way of doing this would be to secure the stones of the wall in concrete before attempting to move it.

As anyone familiar with the construction of the Lakeland type of dry-slate wall will know, it is in fact a double wall, the two sides leaning slightly inwards, with a filling of rubble in between. At intervals there are courses of “throughs”, long stones tying together the inside and outside leaves. So in order to embed in concrete the stones that support the plaster on the inside face, it was necessary to remove the outer leaf of the wall and dig out all the rubble filling. A perilous operation.

First of all the bank behind the wall was dug out, so that work could begin on securing the stones. The whole job was supported continuously by wooden shoring inside the barn and Acrow expanding props outside. These props are easily portable and enabled us to apply support to the outside exactly where it was needed as the job progressed.

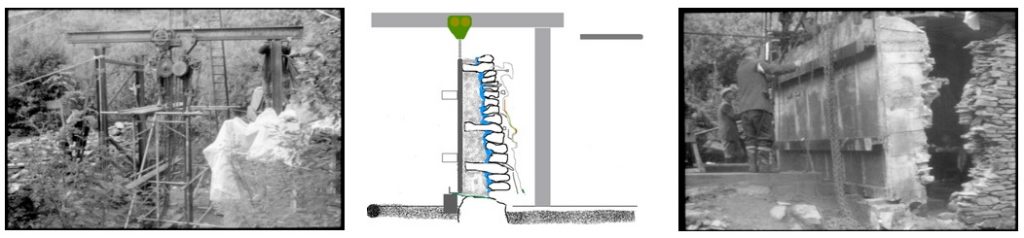

- Cross-section of Merz Barn Wall in situ, earth bank behind double-leaf drystone wall, rubble infill, intermittent through stones, plasterwork on interior wall.

- Earth bank dug away. Internal timber shoring in place, cushioned with foam blocks. Acrow props outside.

- Timber shoring inside the barn to support the wall while work is under way on the outside.

Working in sections about two feet square at a time, the outer wall and the rubble filling were removed, and the exposed backs of the stones of the inner wall grouted with a strong mortar. Each section treated this way was then left for several days to set while work continued on another part of the wall. The wall which was eventually moved measured about thirteen feet by nine, and this initial stage took about a month to complete.

- Process of removing outer leaf of stones begins, removing rubble, grouting exposed backs of inner leaf stones.

- Removing the outer leaf of the wall progressively in sections

- Ted, Laing’s foreman on the project, at work grouting the back of the stones of the inside wall

Our problems were complicated by the fact that the wall, though relatively recent (it was put up in 1943) stood on old foundations. These consisted of large boulders set deep into the ground. They were judged too large to be moved safely with the rest of the wall and so a division was made to clear the tops of them. This meant losing the lower twelve or fourteen inches of the inside face, which, fortunately, contained no features which could not fairly readily be replaced. Furthermore, on the north side the barn was built in to the hillside, and this necessitated leaving behind the right-hand end of the wall about two feet from the corner. This part of the mural had been left in a very unfinished state at Schwitters’ death and had been subsequently worked on by Mr. Pierce and his associate Jack Cook, to help make it more permanent.

- Outer leaf completely removed, grouting complete, through stones propped

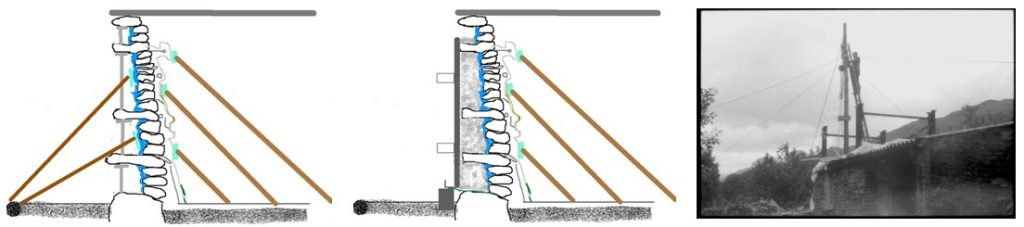

- Through stones cut back, steel frame erected, and shuttered, filled with concrete, sill cast in place at foot of frame

- Tommy Niven up the pole hoisting the gantry into place.

So that it could be moved, the wall needed to be in a stable horizontal position. The plan was to tip over onto its back the completed steel and concrete mass with the wall embedded in it. The next stage of the removal was therefore to erect a steel girder frame behind the wall which would be incorporated into the concrete and provide lifting points as well as reinforcement. A concrete sill was built on which the whole thing would eventually heel when it was lowered. The erection of the steel frame was hindered by the presence of the ‘throughs’, several of which intersected with the steel frame or projected beyond it. We realised that these would have to be cut off. The risk of vibration damaging the plaster was very great, as the fabric of the mural was in a very fragile condition.

To prevent this as far as possible a fibre grinding disc was used rather than a metal saw. This had a certain degree of flexibility and did not catch and jar as a saw might have done. The stones were cut by Ted, the foreman, successfully and without incident (other than my own blood pressure.) With the steel framework up, it was shuttered and filled with concrete, mixed on site (it was inaccessible for a ready-mix lorry).

- Lifting gear being hoisted in to place on the gantry

- Roof opened, gantry erected, lifting tackle in place, lower section of plasterwork removed, foundation joint raked out

- The wall stands ready to be moved

The next stage was to put up a gantry over the site to carry the lifting gear which would be used to lower the wall to the ground. Since the weight had been estimated to be as much as twenty-five tons, this had to be a mighty structure. The terrain posed problems. The barn stood about one hundred and fifty yards from the road and could only be reached up a steep slope and along a grass track with a wall on one side and a ditch on the other. It was impossible to bring up a crane and so all the steelwork had to be manhandled into position with a block and tackle hitched to a pole.

As the job progressed the weather, which had been good, worsened and we had heavy rain during all the vital stages of the removal. After a great deal of heaving and struggling the gantry was up. It must have been twenty feet high and the girders on top carried four huge sets of lifting tackle which were attached to the lugs welded to the top of the steel frame now cradling the wall. A cover of tarpaulins was thrown over the gantry to keep off rain and all was ready. The weight of the wall was taken on the gantry, and the joint at the bottom of the inside face was raked out. Wedges were placed along the bottom of the wall to help prevent it from skidding forwards as the wall was lowered. The lifting tackle was run slowly backwards along the gantry keeping pace with the top of the wall as it went over. Slowly, slowly the mass began to tilt and finally settled onto blocks of wood on the ground.

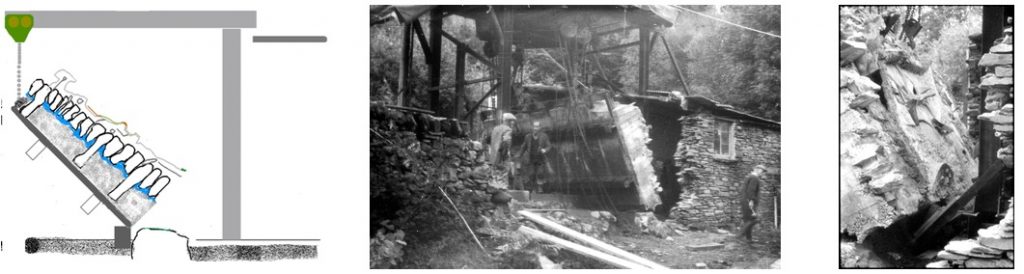

- Entire block is tilted over to the horizontal ready for removal

- Sid, Tommy and Ted, as the wall tilts (a test run the day before the press were invited)

- For the first time the wall artwork is exposed to the outside

The preparatory stage was completed.

Transportation

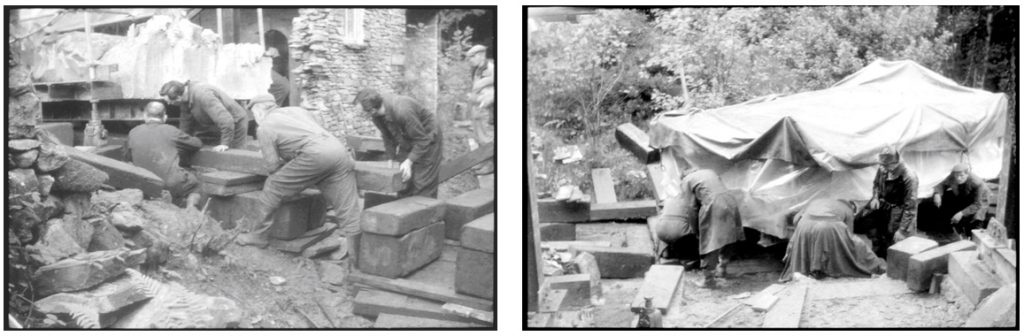

A frame of scaffolding was erected over the face and covered with polythene sheets and tarpaulins, to try to keep it dry. Pickfords, who were the contractors for the transportation, arrived in pouring rain and found the going too muddy for their lorry, it had to be hauled up by a hand winch to a point where the track levelled out. A road of railway sleepers was laid over the remaining section, and the actual move began.

The process consisted of jacking up the Wall, laying steel plate tracks on blocks of timber underneath it and sliding it on ‘skates’, sets of steel rollers in a frame. The Wall had to be hauled to the pathway, turned through ninety degrees and lowered down a six-foot drop before reaching the relatively straightforward track, still in the pouring rain.

- Pickford’s team, led by Leo , begin to move the wall out

- In pouring rain, the wall edges towards the pathway to the road

The Laing’s team led by Ted had spent months with the wall (and with me) and had come to understand the nature of what they were handling. The Pickford’s men, led by Leo, were experts in shifting enormously heavy electricity transformers for substations across fields and wild places. For them this job was another heavy weight to be moved, and I had to begin over again, in a hurry. As the block of concrete with Schwitters’ last work embedded into it began to move, winched along the track towards the pathway, it started to run slightly off line. I saw one of Pickford’s men reach down for a sledgehammer and prepare to give the block a tap to straighten it up. I had to throw myself between him and the Merzbarn, and explain that we were not going to do that. After a short consultation, it was agreed that instead of whacking it, a little hydraulic jack could be used to apply such pushing as was needed.

All went well and the wall was winched slowly out and eventually on to the lorry. Driving it out fully laden was a different matter from getting the lorry in, which had been difficult enough. With the Wall on board, on ground soaked by days of rain, as it crept down the pathway towards the road, the lorry began gently to slip sideways down the slope, as the pathway broke up beneath it. I was in front of the lorry and could see the face of the driver. He registered the problem and I saw him take an instant decision. Had he stopped, the whole thing might have slid uncontrollably sideways. He held his nerve, pressed on, brought the load gently round the bend to face downhill to the road, and out.

- The wall is hauled down a track of sleepers to the lorry. Press photograph

- The laden lorry manoeuvres its way out of Cylinders to the road

- The scar the load left on Clappersgate bridge on its way to Ambleside. Photo: Mary Burkett

One more hazard was to come. At Clappersgate, the road from Elterwater to Ambleside crosses the beck, a sharp right and left turn over a humpbacked bridge. Coming, the low loader had managed to manoeuvre the bends and cleared the bridge. Going, laden, the bottom of the trailer chewed a deep groove in the roadway at the peak of the bridge, but made it over. Mary Burkett, following the lorry, took a picture. From there it was comparatively plain sailing. Getting the wall onto the lorry and out to the road took about a week in all. The lorry with the wall and myself aboard left Cylinders at three o’clock in the afternoon, made an overnight stop in Kendal and on the morning of Monday, 4th October, it arrived at the site in Newcastle.

Press photo of the Merzbarn passing Darlington en route to Newcastle

In 2008, the Dutch artist team Kunstgeographie built a website examining the move, including a film tracing the route it took. At their request I obtained some maps dating from the time of the move and drew out the route that the Merz Barn Wall took, as best I could remember it. Those maps are included in the Appendix.

On arrival in Newcastle the Wall was offloaded by a crane, and stored in a horizontal position on a patch of empty ground at the corner of King’s Walk and Claremont Road, about fifty yards from where it is now. A hut was built over it to keep out the weather and a thermostatically controlled electric heater was installed underneath to protect it from frost and to help dry it out. The hut was closed and no more was seen of the Merz Barn Wall until the following year, 1966.

Into the Hatton

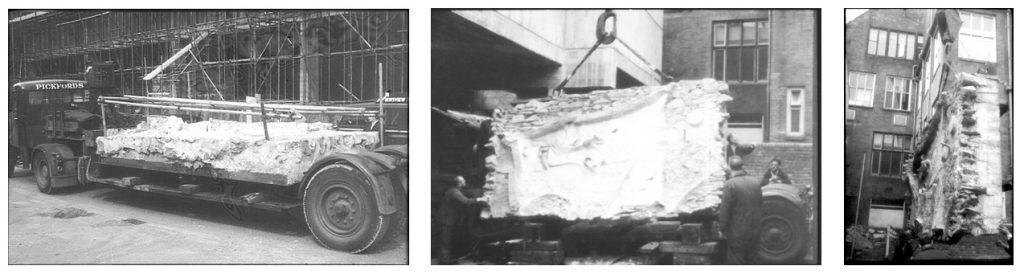

It was on Schwitters’ 79th birthday, 20th June 1966, that the Wall was moved for the last time. There was much to be done to take it from its temporary berth on the corner of King’s Walk and Claremont Road to its final home in the new Hatton Gallery. The shed that had sheltered the Wall over the winter was dismantled and the block craned on to a waiting low-loader to take it the 50 yards to its new home. In advance a huge road crane that would hoist it four stories high was manoeuvred under the bridging block of the new building, followed by the low-loader backed into place below the eventual site.

The plan was to lower the Wall in to the gallery from above.

- Cross-section of the alcove built out from the side of the new Hatton Gallery, open at the top, to receive the Merzbarn

- Merzbarn to be lowered in to place from above through narrow gap

- Merzbarn in place in the alcove, sitting on raised sill, secured to rear wall, roof closed above

The rear wall of the alcove, against which the Merz Barn Wall would stand, had already been built, and its roof was left open. The opening was a narrow slot the shape of a letterbox, through which the wall had to be lowered from above. While all that was getting ready, I took a rule to the opening at the top of the alcove into which the Wall was to be dropped and found that it was narrower than the widest part of the Wall by about eight inches. The design had been based on dimensions and weight specified to the architects, but could only have been estimates, since the preparations for removal would hardly have started at that point. The estimated weight may have meant that no more than a certain overhang could be accommodated. Whatever the reasons, as it turned out, there was no choice for me but to take a hacksaw to the Merz Barn Wall and cut off the most prominent part, at the left-hand end, to allow the block to enter through the gap. I put it back in place during the restoration work later, along with several other components that I had taken off for safe-keeping to prepare for the move.

- The Wall waits on its lorry, ready to be hoisted in to the new gallery, still under construction

- Lifted into the vertical by a huge crane, below the alcove where it will be installed

- Swung into alignment ready to go up

The destination stood at second floor level over the roadway on which the Wall now lay, back on its lorry, ready to be lifted up and over the back wall of its alcove, facing against the blank wall of the gallery above, and slid down through the gap. The inside of the back wall had been greased in advance to ease its entry. With one of Pickford’s men and myself handling ropes fastened to the bottom corners to try to control it, the Merz Barn Wall was hoisted into the vertical, turned 90 degrees and lifted into the sky. The face of the mural could not be covered because, due the danger of damage to the projections on its face, we had to be able to see it every inch of the way as it was lowered through the gap. A gust of wind could have swung the huge weight against the wall of the gallery above the alcove and smashed it; a shower of rain could have ruined it.

Mercifully the morning was calm and clear. As the Wall began to slide in through the gap I ran up to the gallery to see it in, leaning my weight against it as it inched down to try to ensure that it cleared the slot as the widest parts came through. In the end, this once-in-lifetime job went off without a hitch. The Wall was settled and anchored back to its new wall, the slot above roofed over, and we all breathed again.

Mercifully the morning was calm and clear. As the Wall began to slide in through the gap I ran up to the gallery to see it in, leaning my weight against it as it inched down to try to ensure that it cleared the slot as the widest parts came through. In the end, this once-in-lifetime job went off without a hitch. The Wall was settled and anchored back to its new wall, the slot above roofed over, and we all breathed again.