Above: Conservation project under way 2015, photo ©Colin Davison

Installation

On 20 June 1965, Schwitters’ birthday, the great block of concrete carrying the artwork on its face was lowered in to an alcove built out from the wall of the new Hatton Gallery extension to accommodate the Merz Barn Wall.

It was, as I have said, too tight for depth but generous in width and height. Once in place the Wall itself stood with its back against a large area of concrete, and the surrounding space was to be filled by a new stone wall. I recall travelling on a train to Carlisle one morning in 1966, meeting up with someone from Laing’s and going out to a quarry to choose the stone for the job. I was at pains to explain that we needed rough and ready material, not the worked and dressed stone that was sold for buildings and fireplaces, and so we ended up at a vast pile of broken bits, more or less waste. Nonetheless it was some way away from replicating what the barn had been built from. For a start it was not Langdale stone and was not the same colour. It was all quarried stone that, although irregular, bore little resemblance to the fieldstone that made up a big part of the wall at Cylinders, and it was clean! The quarry was reluctant for us to take what they regarded as poor quality material, but after some argument it was agreed that Laings would bring over a load of random stuff and we would seek to make the best of it.

The quarry was reluctant for us to take poor quality material.

To carry out the job of building up the surrounding wall to fill the space of the alcove, a stone wall specialist was engaged by the contractors. He had already got to work on his first morning by the time I arrived, and I was alarmed to see that, starting in one corner, he had set about building as good a wall as he could with the inferior materials we had provided, carefully laying the cut faces to the front and hiding away the rough bits as much as possible. I stopped him and explained that this was not what was wanted, that the ‘inferior quality’ stone had been deliberately selected to approximate to what the artist had worked on, and that he needed in this instance to rough-up his normal highly finished practice and make it look hasty and irregular. He was none too pleased. It also turned out that he was laying the stone with mortar, rather than dry, which was necessary since it was only a single leaf and reached very high. This meant it was by now too late to pull out the work already done. Sharp-eyed observers may notice the difference.

The new wall made the Merzbarn look shabby (which it was).

Another problem was how to deal with the colour and sparkling cleanliness of the new wall, which made the Wall look quite shabby (which indeed it was). I could think of no other solution, so I mixed up a bucket of mud from the diggings of the building site and roughly brushed over the new stonework to disguise it. That played down the contrast with the old wall somewhat, but there was nothing I could do about the marked lack of the characteristic blunted edges and unworked shapes of the fieldstone that makes up much of the original.

Since the removal plan was designed to preserve and retain as much of the artwork as possible but little else, there is not much of the bare original wall to be seen that is not obscured by plaster, though the vigilant observer will detect the join between the old and the new work.

Conservation

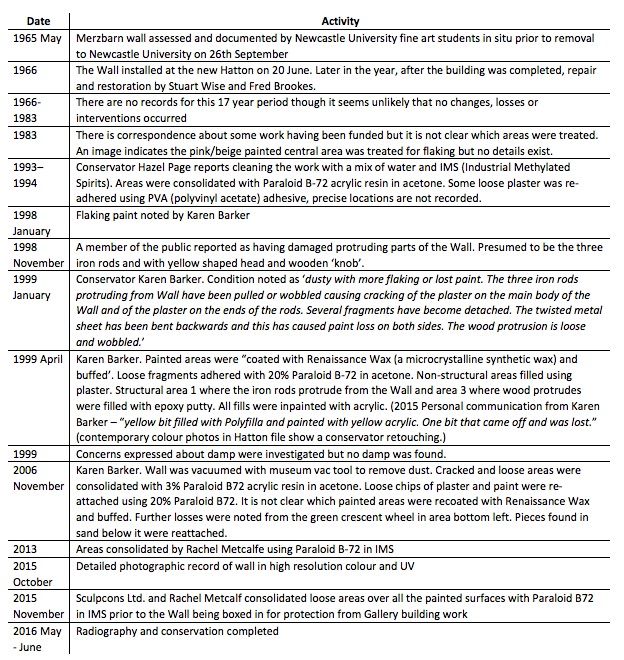

The history of the Merz Barn Wall’s conservation is comprehensively told in the report prepared for the University by Derek Pullen and Jackie Heuman of Sculpcons. Their findings provide an insight into how Schwitters worked on the Wall as well as the various later interpolations The timetable below is drawn from their report.

Work on the Wall

At the time of the survey in May 1965, we had been quite systematic about collecting and identifying samples. I made a measured scale drawing of the whole wall and gridded it up to provide a reference. Each fallen piece of paint or plaster we took from the floor in front of the wall was carefully identified to its original location, as far as we could judge by position, colour and shape, and given a grid reference, which was then written on the brown paper envelope in which each piece was saved. The cardboard box which held all the envelopes, that for many years I thought lost, was found again in the recesses of the Fine Art Department by Rob Airey, then the Hatton’s curator, when the major work was being planned in 2015, and proved very useful to the conservator team.

In 1966 then, first of all, once it was secured in its new home, the alcove where it sits was closed off while building work on the extension to the Fine Art Department building was completed. After that, it was possible to review the state and condition of the Wall in detail and set about the task of repair, restoration and conservation.

This was carried out by Stuart Wise, by then on the Fine Art Department teaching staff, and myself, then a 3rd year student, beginning in the summer vacation of 1966. One of the first things to be done was to replace the parts that had been taken off to admit the Wall through the gap at the top of its alcove and make good the repairs. The chief problem though for the restoration was that over the years, due to changes in humidity and temperature, and perhaps frost, the painted surface of several large areas of paintwork had sprung away from the underlying plaster.

Over time, due to changes in humidity and temperature, the painted surface had sprung away from the underlying plaster

The surface consisted of the top skim of plaster and a skin of oil paint and white pigment wash. This shell was extremely fragile and had, not surprisingly, broken in several places, leaving holes. There were voids behind these areas and, since it was judged to be too risky to try to shrink the top surface back onto its support these voids had to be filled. Having taken advice from Murray MacCheyne, Master of Sculpture in the Department, and from the Tate Gallery’s conservation department, we judged it was possible to fill the voids with a mixture of PVA adhesive and french chalk, which would provide a stable but still slightly flexible solid. All cracks and gaps were carefully closed with plasticine and, by using a large hypodermic needle (a horse needle I believe), the mixture was inserted. A small test area was completely solid after two days and work went ahead on the rest. Once some solid base had been established, the holes in the surface where the plaster and paint surface had broken away were made up with fine plaster and PVA using a small painting knife. Where there was substantial damage the forms were built up to their original shape using our photographic survey and measurements as a guide.

Once all the filling and repair work had dried the problem was to retouch these parts to match the colour of their surroundings. This was a long and tedious business, mixing colour after colour to achieve the best match, referring to the colour samples and matches we had taken in 1965. Eventually satisfactory results were obtained.

A further problem was that of reconstructing the areas which had been lost in the removal, the lower fourteen inches and sections at either side. I had taken clay ‘squeezes’, and made rough casts of these parts on site, but they proved unsatisfactory since the white plaster of which they were made could not be successfully stained to match the original. I decided, therefore, to restore these parts by hand, in the manner, and using the same technique, as Schwitters had used. He had applied the wet plaster with a knife in a rough free way, showing the marks of the tool very strongly. The parts I had to recreate had not been much worked over and so it was possible for me to imitate the original quite satisfactorily. The worst problem here, in fact, was to match the colour of the original material. I sent a sample lump for analysis by the laboratory of British Gypsum Ltd. in Kirkby Thore who identified it as one of their products. Since 1947 however the manufacturing process had been so “improved” as to completely change the colour. It was now pink. We had therefore to make a long series of experiments, mixing pigments with the plaster, and leaving samples to dry, in order to check the match: eventually a satisfactory resemblance was achieved.

Since 1947, the plaster had been so 'improved' as to change the colour. Then gray, it was now pink.

We had to be wary of doing too much work; to make the Merz Barn Wall look new would have been an error. On the other hand it had to be made strong enough to resist further decrepitation, though the risk was greatly reduced by the controlled environment that now surrounded it. We hoped that we had achieved a balance.

One thing we did not know, and which has been pointed out to me recently, was that best conservation practice requires that retouching or making good of damage must be carried out using material distinctly different from the original, so that, while not superficially visible, the presence of interpolations can subsequently be determined. In short this means, for example, retouching damaged oil paint using acrylics, so that the new work can be distinguished from the old (by infra-red imaging for example). Back then we thought the job was to make the repairs as much as possible like what had been there before, so we used oils, making the job of later conservators more problematic.

Building dust being removed in 2016, Photo Sculpcons Ltd

In 1966 after installation the roof above was closed and the alcove in which the Wall sat was screened off and taped up. Nonetheless, by the time the building work was complete and we opened it up to begin the restoration work, we found it had a thick layer of gritty dust. Similarly, the Wall was boxed in for the duration of the 2016 building work but on opening up was found to have much the same. The conservators carefully vacuumed it off. We did not have museum standard vacuum cleaners in those earlier days.

What we have

As a result of the removal works and the subsequent restoration and conservation, and the development of the building around it, the Merz Barn Wall as it stands now is a cocktail of Schwitters’ own hand, work done by assistants under his direction, additions and subtractions made after his death by Mr Pierce, the reconstruction and repairs of 1966, an addition by a later hand probably in the 1970s, and conservators’ work since then to the present time. It is not possible to be entirely sure about what parts belong to which category, but the image below gives as best an indication as I can produce of what remains of the work as it stood in 1965 before the removal was undertaken, the later work being greyed out.

Photo ©Colin Davison 2017, interfered with by FB 2019

Exhibition

Once the initial restoration work ended, early in 1967, the Merz Barn Wall was on public display and it began to find its place in the Hatton’s collection and programme. The Hatton collection is a very diverse accumulation of acquisitions thatincludes sculpture, paintings, watercolours and prints from the 14th century to the present day. It has benefitted from the many contemporary artists who have been associated with its ambitious temporary exhibition programme and the teaching in the Fine Art Department to which it is attached. The Wall came by a different route, and it was some time before its nature and significance were fully accommodated into the collection.

There is relatively little sculpture in the collection and it became clear that a large and immoveable object was not always going to fit easily with the display of the collection and particularly the adaptation of the gallery spaces to accommodate the wide range of incoming temporary exhibitions of loan works. Furthermore, at the time of its acquisition there was little academic or critical work on Schwitters, and most of what there was focused on the earlier German period of his output. Being late, remote and very different in its nature from his earlier work, the Merzbarn was little known and authors who mentioned it at all tended at that time to dismiss it. Now that was accessible, its relationship to the artist’s body of work could be explored, and academic and critical appraisal began to grow.

Programme

Though it was not always the case, there have been many instances when the Merz Barn Wall and the Hatton’s link to Schwitters and his world was celebrated and featured strongly in the programme of events, exhibitions and performances that took place in the gallery.

The Hatton’s interest in Schwitters was evident as early as January 1959, when the large exhibition of collages and sculpture organised by Philip Granville at his Lords Gallery in London was shown here. Later instances included an exhibition of work by artists interned in the Isle of Man camp in 1940-41, “His Majesty’s Most Loyal Enemy Aliens” opened in May 1991, featuring the Merzbarn alongside other works of Schwitters and his former companions. An exhibition titled “Wall to Wall” in February and March 2014 was a collaboration between Film and Video Umbrella and Hatton Gallery, and included new work inspired by or related to the Merzbarn.

I occasionally featured in the Hatton programme myself, talking about the Merzbarn and performing sound poems by Schwitters, including a performance for an exhibition of Dadaist avant-garde works in September 1999. Distinguished visitors to the Hatton have on occasion written about their experience. An example is Ithell Colquhoun, the surrealist painter, writer and occultist who visited the recently-installed Wall in the Hatton in 1968.

By the 1960s, the wet and cold of the climate had caused such serious deterioration in the wall itself that the authorities of Durham University transported it en bloc – a difficult feat of engineering – and set it up in their new Art Department at Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

When I saw it a year ago (1968), in an environment of regulated temperature and humidity, it was tended by a Beardsleyish faun – named (incredibly!) Fred Brookes – who might have sprung from the art-nouveau brickwork of the older buildings across the lawn. On the staff of the sculpture school, he was repairing the wall and explaining it to interested visitors. Its preservation is important since it is now the only comparable work of Schwitters to survive, the one constructed in 1937 at Lysaker near Oslo having been destroyed by fire a year or two back.

In and out of sight

The Merz Barn Wall’s significance as a major part of the University’s collections and a historic piece was not always as much appreciated as it is now. According to reports I have had from various people closer to the Hatton than I was at the time, and from its archive, there were periods when it was not on view, being covered by more-or-less temporary screens to provide additional exhibition space in the gallery. Correspondence makes it clear that there were periods when the Wall was screened off from view and the space used for exhibition of other works. It was covered for a period in 1971. In 1978 Ernst Nündel, a distinguished Schwitters scholar, wrote to complain that, having come 1000 miles to view the Merz Barn Wall, he had found it shut away behind a large exhibition of Russian art.

For a period of about six years from 1993 the Wall was enclosed in a small room built across the front of it, cutting it off from the rest of the Hatton exhibition space. It could be accessed, when available, by a door from the gallery. This led to a vigorous exchange of correspondence between the Hatton and the Observer. Its art critic, William Feaver, who knows the work of Schwitters and his period in England very well, was a member of a press corps invited to preview an Arts Council acquisitions exhibition in the Hatton in March 1996. He reported opening the door to the Wall’s little room, and finding

“Behind a door and partition, in a glorified boot cupboard, there’s a clutter of dumped sculpture, timber, a trolley and other odds and ends. Beside these, unprotected, is one of the key works of twentieth-century art … It’s scandalous that this touching and inspiring work should be taken off show, shut away like an embarrassment. The Hatton can plead security concerns and lack of space and poverty, but that doesn’t explain the rubbish and the neglect.”

Feaver’s account brings to mind earlier times when the Merzbarn was a storeroom. It has more than once been obscured by extraneous stuff. A heated correspondence between the Hatton’s director and the Observer ensued, the newspaper standing by its critic’s report. The ‘boot cupboard’ was eventually removed in April 1999, for the large ‘No Socks’ exhibition that was jointly organised by Hatton and the emergent Baltic, then under construction, as part of the run-up programme to the latter’s opening in 2002. An order to the University’s maintenance department shows the layout of the enclosure.

Source: Hatton Archive

Later still, the upper level of the central gallery suffered structural problems and had to be closed, and other technical and practical problems with the building worsened to the point where full-scale refurbishment was conceived.

A close shave

In June 1997 the council of Newcastle University, in pursuit of spending reductions, took a decision to cease funding the Hatton Gallery, with the intention of closing it to save £45,000 a year. The fate of the collection, and in particular the Merz Barn Wall, which is effectively not portable, was not made clear at that point. The following day, however, the famous north-east novelist Dame Catherine Cookson, who had a long philanthropic association with the gallery and the University, offered a donation of £250,000 spread over five years, if the University would agree to keep the gallery open. It did.

Management

Enter TWAM

In 2002, approaching the end of the period for which Dame Catherine Cookson had guaranteed the continuation of the Hatton, the opening of bidding for the European Capital of Culture 2008 prompted the University to develop a vision for how it might seize the opportunity to develop its cultural activities and amenities.

The bidding process brought together a coalition of interests including Newcastle City Council and Newcastle’s two Universities together with the Newcastle Gateshead Initiative. Following the completion of the Baltic Centre for Art in 2002 and the Sage Music Centre in 2003, it was questioned what capital projects would become the cornerstones of a Newcastle/Gateshead bid. It was agreed that consolidation, upgrading and expansion of the cultural facilities on University of Newcastle campus could offer a boost to the City’s cultural facilities, and would be a good fit in terms of proposition and project timescale for the 2008 bid. This was in any case necessary given their condition at the time. This became the Cultural Quarter project. AEA Consulting was appointed in July 2002 to further develop the vision and detailed proposals for the project, reporting to a steering group led by the University of Newcastle, and produced an Options Appraisal in 2003.

The Hatton Gallery figures strongly in the initial vision created by the University, and to some extent in the options appraisal for the Cultural Quarter, though more attention there is given to the Hancock Museum, then badly in need of capital investment. At the time, the Hancock, which belongs to the University, already had a management agreement with the then Tyne & Wear Museums Service. The report also considered how to resolve the location of the two other specialist museums within the University, as well to the potential for developing new buildings for exhibitions and public participation. The point was made that a new front for the Hatton, giving it a stronger public presence and a new entrance facing the city centre, was desirable.

Newcastle/Gateshead’s bid made the shortlist in October 2002, but in the event, Liverpool took the title, and the Cultural Quarter project did not come off as had been hoped. Nonetheless some elements of the bid were pursued, and the Hatton’s development was among them. The University brought together a steering group to work on a major bid to Heritage Lottery Fund in which Tyne & Wear Museums was involved.

Since the abolition of Tyne & Wear County Council in 1986 Tyne & Wear Museums had operated as a managing agency for museums across the region, later merging with the archives service to become Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums (TWAM). As discussions continued the concept of the Hatton and other University museums coming together under the management of TWAM strengthened, and by late 2003, not without some tensions, a deal was being brokered. By spring 2003 a large-scale and detailed proposal to HLF was being worked up, with the Hatton as a major element. Part of the concept was that the whole of the University’s museum and gallery operations would be included in the Great North Museum project, managed by TWAM. In October 2003 TWAM’s director wrote a long letter to the University’s Deputy Vice-Chancellor setting out in detail the way in which TWAM would approach taking on this role, against a background of its long and successful record of management of museums and archives. This letter confirmed the substance of previous discussions and set out with candour the terms on which an agreement could be struck. Ultimately this proposition prevailed, though in the event it was another four years before the Hatton became part of the Great North Museum portfolio.

The redevelopment project launched on 25 February 2016 (the Hatton kindly invited me to speak at the closure of the gallery) and re-opened on 10 October 2017. The significance of all this for the Merz Barn Wall was to be enormous. An integral part of the £3.8m programme was to be the first thorough professional appraisal and conservation of the Wall since it was installed fifty years previously, and to reshape the way it is presented in the gallery.

Physical accommodation

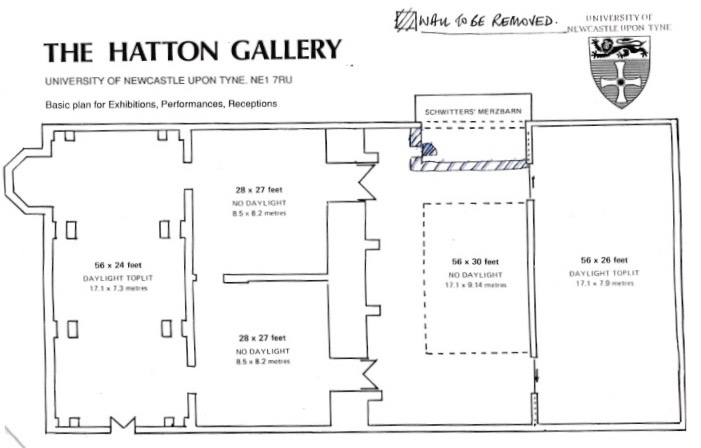

While it is obviously not a portable artwork, nonetheless the Merz Barn Wall keeps on moving. Its location has been fixed to the spatial co-ordinates since 1966, but the building has been shifting around it. The gallery that houses it has moved several times around the still centre of the Wall. This section sets out what I know of the story, drawn from archives and interviews.

The first situation of the Merz Barn Wall in the newly-built extension to the Hatton Gallery could hardly have been more different from its original site. The barn was a small, quite intimate, dark and remote place. The Wall now found itself in a busy urban academic environment, on the wall of a wide corridor, illuminated by a large south-facing plate-glass window, with passing foot traffic to and from the main gallery spaces. This presented some problems. The strong daylight posed the risk of fading and of possible further decrepitation in the very dry atmosphere. There was some risk to security as the location was not directly supervised. There was no sense of the contained space of the original site nor any indication that the work was part of a larger conception. There was little in the way of interpretation or explanation of what it was and why it was there.

In the mid-1980s the Hatton was remodelled. The elevated sculpture court was incorporated into the interior of the building and roofed over, becoming a new large gallery space (now the education room). This meant that the Merz Barn Wall no longer faced a huge south window but was in a much more controlled light.

In 1998 a further re-display and enclosure for the Wall was evidently being considered, with correspondence between the University and the Ryder architectural practice, and the offer of £10,000 from the Henry Moore Foundation. This does not appear to have been carried through at the time.

The Merz Barn Wall attacked

Around this time in November 1998, the Merz Barn Wall suffered an attack by a gallery visitor. I have not so far been able to discover who or why. It is clear from the notes made by the conservator, Karen Barker, who was brought in to do repairs early in 1999, that several parts of the work were deliberately damaged. She notes “The three iron rods protruding from Wall have been pulled or wobbled causing cracking of the plaster on the main body of the Wall and of the plaster on the ends of the rods. Several fragments have become detached. The twisted metal sheet has been bent backwards and this has caused paint loss on both sides. The wood protrusion is loose and wobbled. One bit that came off was lost.” Loose fragments were re-adhered, damaged areas were filled with epoxy putty and all fills were re-painted with acrylic.

2016 Redesign

This was a major project for the Hatton, which had profound implications for the Wall. It enabled a full-scale and up-to-date appraisal of the art work, its condition and the need for conservation, together with a reconsideration of its place in the Hatton collection, and of the way that it is presented and cared-for. Neil Greenshields of LDN Architects, Edinburgh, who undertook the redesign and refurbishment of the Hatton, told me in 2019:

Our treatment of the Merz Barn Wall gallery very much developed in the course of the design. Three of us from the LDN office visited the old barn in Elterwater to see what its original situation had been, and with that in mind we had to come to terms with what was really possible within the existing concrete structure of the Sheppard Robson building, and the desires of the various stakeholders.

The size of the new space around the Wall is now about the same as the barn. At one stage we proposed putting two openings in the new walls that would match the size and position of the windows in the barn. Our suggestion was to make pieces of wall that could be removed when the openings were wanted. The users, however, wanted to use the other side of those walls for permanent display, and not have anything interrupting a plain wall.

Initially the client had wanted to open up the space and take away the low section of ceiling that sits opposite the Merzbarn. This ceiling area however is a large mass of concrete that was once a roof, forming part of the bridge-like structure around the courtyard. To remove that would have been a significant and costly undertaking. The anticipation that vibrations from the demolition might damage the Merzbarn effectively knocked that idea on the head. Once that confinement was accepted, it made a more reasonable proposition of creating a small room around the artwork.

Rob Airey, the curator at the time, wanted to echo the dark space of the barn that the artwork jumped out from when you entered, so together we chose the dark walls, and a good light on the subject which avoided casting viewers’ shadows on the artwork. Richard Talbot, in the Fine Art department, wanted the option of flooding the space with light for study purposes, and so large ceiling lights are also available in the space for those times.

There is also some additional security on the artwork, a light beam that visitors might trip if they move too close.

TWAM’s requirement for particular environmental controls around the work was one thing that prevented us from completely opening up the space to have it sit within a larger area or doing more ingenious things with the walls.

The Hatton re-opens

After its capital works, the Hatton Gallery re-opened in October 2017. The Guardian’s arts correspondent Mark Brown wrote:

A gallery that contains what for some is the most thrilling, important and influential piece of postwar modernist art ever made in Britain is about to reopen after nearly two years of closure.

The Hatton gallery, founded in 1925 and part of Newcastle University, has undergone a £3.8m refurbishment ushering in what should be a new era. While the gallery is internationally important, it has for decades been hard to love and difficult to find.

It will finally reopen to the public on Friday next week with an exhibition exploring the role Newcastle played in the rise of pop art. But for many art lovers, the chief draw will be the chance to see Kurt Schwitters’s restored Merz Barn wall, a modernist masterpiece that was rescued and installed at the Hatton in 1965.

The 20-month redevelopment, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, has created bigger spaces that are airy, bright and pleasant – a far cry from the old Hatton. “There were no environmental controls; the lighting was terrible,” said Richard Talbot, head of fine art at the university. “The fittings were such you couldn’t even get the bulbs for them.”

Julie Milne, chief curator of the city’s art galleries, recalled the complaints from visitors. She said: “Most of the feedback we got was about the gallery’s gloominess. There were wires all over the place and lumpy walls, which were difficult to hang on. Intrinsically, the building is beautiful – it was just very shabby and run down.” . . . Over the years art lovers have made pilgrimages to the Hatton to see the Wall, but the lack of environmental controls was putting it at risk. It has now been conserved – 52 years of dust removed – and its setting improved; a slate-grey floor has replaced the red wooden parquet. “It was incredibly grimy and looked quite dark,” said Milne. “Now it has been conserved, it is amazing how bright it looks.”

What next?

The outcome of the redesign and restoration project is a great improvement on earlier conditions. Lighting is better controlled and maintained at a level that encourages conservation, as compared to being bathed in daylight as it was when first installed. The place it sits in has ranged from a wide gallery to a small cupboard, and has now settled on a space about the same size as its original home. Security has greatly improved, and there is a display to provide a context and background to help the viewer understand and interpret the art work, as well as something of its complex history.

There are some aspects that in my own view would benefit from further consideration and change. The floor area immediately in front of the Wall is laid with a coarse gravel or aggregate to discourage visitors from stepping too close to the artwork. That is sensible enough but at present this material is visually very close in tone and texture to the loosely-handled plasterwork on the lower part of the Wall, and so loses the line of the foot of the work where it meets the floor. The display would be improved by using a darker material to achieve the same security objective while better defining the shape of the bottom edge of the artwork.

At the left-hand end of the Wall, there is a return stub of stone wall that was built at the time of the restoration to carry the reconstructed parts in that area. The grey gallery wall that now encloses the space at that end is set in alignment with the outside face of that piece of wall. This creates the false impression that the exposed stub is an element in the artwork. In my view the grey partition wall should be aligned with the inside face of the stone wall, corresponding to the situation opposite, at the right-hand side. I cannot think why it was not built that way in the first place.

Lighting is not yet fully developed. The general gloom now surrounding the Wall puts it in the right context, but in my view an opportunity is being missed to manage and control the way light falls on the work. At present lights above the viewer cast many shadows of the higher-relief parts on to the surfaces behind, which for me is wrong both because it was never lit like that originally, and because the multiplicity of shadows interferes with the form and colour. A way of letting light in as it fell from the three sources in the barn, the north and south windows and the skylight, could be found. With some technology, the shifting conditions of light through the day and the seasons could be incorporated. The present skylight already does this to a degree, though the orientation of the Wall is about 90° out from the original (facing south rather than east), and so daylight falls inappropriately.

Two further points may be worth a mention. When first exhibited to the public, the Merz Barn Wall contained a couple of things that have since disappeared. I would like to propose their re-instatement. Detail is given in the Addendum: the gentians and the ping-pong ball.

The Merz Barn Wall is in excellent, competent and well-informed hands. The above are my personal observations and we should all be thankful that decisions about its future are not down to me.